A New Account of Israel–SDF Ties Raises the Stakes for Syria’s Northeast

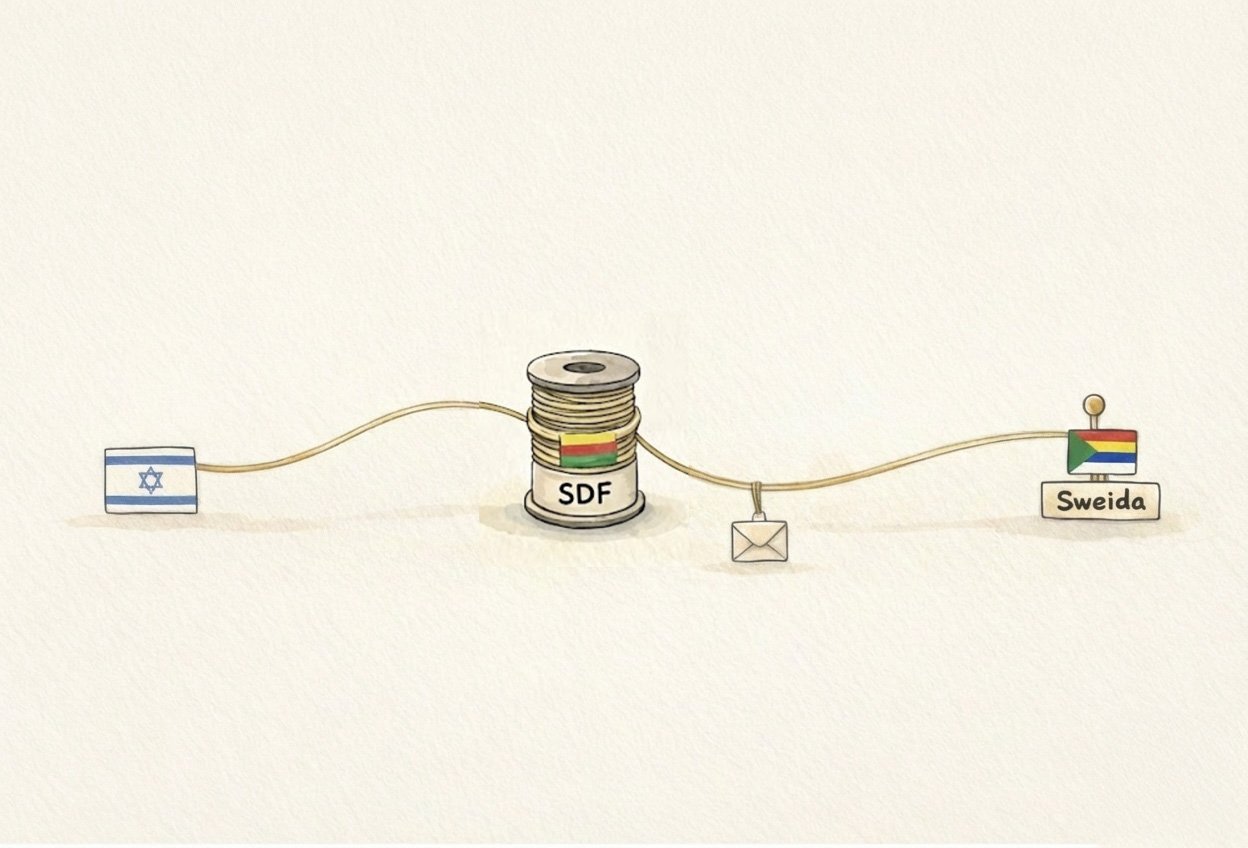

The Washington Post reports that the SDF “maintains ties to Israel,” and that Druze figures linked to Israel’s security establishment funneled money to Druze militants in Sweida via the SDF just months before the collapse of the Assad regime. This is the most explicit and operationally specific report by a top Western outlet to cite Israeli and Druze military sources describing a channel that runs through the SDF, rather than treating Israeli Kurdish outreach as a matter of political sympathy or vague contact.

The report comes one day after Turkey’s foreign minister Hakan Fidan, speaking from Damascus, accused the SDF of “coordination with Israel,” which he described as the biggest obstacle preventing implementation of the March 10 agreement that stipulates the SDF’s integration into the Syrian army.

Context: The Washington Post report represents the most concrete evidence of SDF-Israeli ties published to date. On December 15th, the AP reported that Israel “made overtures to Kurds in Syria,” though without providing the kind of specific operational details the Post has now offered. In December 2024, Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar publicly acknowledged that Israel is “in contact” with Kurds and Druze in Syria. In January 2025, the Israeli newspaper Israel Hayom reported “an extensive phone discussion” between Sa’ar and Ilham Ahmad, the foreign minister of the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Syria.

Analysis: What makes the Washington Post’s reporting significant, even though its primary focus is on Syria’s Druze ties with Israel and the SDF information appears as a peripheral detail, is that it provides the most explicit evidence yet of an operational relationship. The report cites both Israeli and Druze military officials, and its details suggest a pre-collapse, continuing operational channel rather than mere “ties.” This is the first time a top-tier outlet has laid out a specific, time-bound mechanism that portrays the SDF as a conduit and trainer for a partner of Israel in southern Syria.

The story’s details matter in two important ways. First, it clearly suggests the ties were established before Assad’s fall, meaning the SDF was not simply reacting to a new Syrian order but was already functioning as a node in a contingency network. Second, the piece suggests these ties continue today. The Post notes that “up to half a million dollars were separately sent by the SDF to the Military Council.” Even setting aside the Israel angle, this indicates the SDF may have been an active financier or partner, not merely a pass-through. The word “separately” is significant: the Post is presenting this as an additional channel, not simply the same Israeli money. Furthermore, the report states that the SDF trained Syrian Druze, including women, in Kurdish areas and that the relationship “continues to this day,” according to a senior Kurdish official, a Druze commander, and a former Israeli official. In sum, the outlet is describing the SDF as an operational middleman through which Israeli-linked support moved inside Syria before Assad’s fall, a relationship that allegedly persists.

For Israel, this is neither new nor surprising. It represents the continuation of decades of engagement with Kurdish movements, an expression of David Ben-Gurion’s “periphery doctrine,” which aimed to build alliances with non-Arab regimes and minorities across the Middle East. From an Israeli perspective, it makes strategic sense. But the fact that the relationship has advanced this far suggests Israel no longer sees a viable path to mending ties with Turkey, for whom the SDF and, by extension, the PKK remain core national security concerns.

The complication is more acute from the SDF’s side. Turkey has long alleged SDF ties with Israel, and evidence of explicit operational coordination may harden Ankara’s stance. While from the SDF perspective such ties with Israel and other Syrian minorities serve as a hedge against the centralization push by al-Sharaa and Turkey, this kind of exposure could push Turkey toward harder action or force Damascus to adopt a maximalist position on dismantling the SDF.

From an SDF perspective, external ties function as an insurance policy if U.S. protection proves uncertain. But exposure comes with costs. Publicly, this kind of reporting can become a poison pill. It undermines SDF claims to being a purely Syrian actor and risks alienating Arab constituencies in places like Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor, where the stigma of being “Israel-linked” is politically toxic. It strengthens Turkey’s argument that integration must mean disarmament and command breakup, not cosmetic rebranding, especially given that it supports Turkish claims that the SDF is becoming part of a southern flank encirclement designed to weaken the country.

The SDF leadership has denied ties with Israel, and Reuters has quoted Mazloum Abdi saying the SDF has no links with Israel, even while arguing he would prefer good relations with all neighbours. That leaves the struggle not only on the battlefield and at the negotiating table, but in an information war over who is sovereign, who is foreign backed, and who has the right to carry arms in the post Assad order.