How a bitter Washington divorce unravelled the secret U.S. fortune of the Barzani brothers

In a sprawling series of federal lawsuits filed between August 2023 and late 2025, Mahtaub Moore — a former Republican congressional candidate and veteran political operative — has alleged that her husband acted as the legal architect of a vast, off-the-books financial empire tied to the sons of Masoud Barzani, the Kurdistan Region’s most powerful family.

What makes the litigation unusual is not only who she names, but what the marriage appears to have been fighting over. The breakup was ugly, and in the court record it repeatedly turns on a disputed trove of documents, materials her husband allegedly tried to claw back and contain as the relationship collapsed. In Moore’s telling, those papers were not incidental. They were the infrastructure: corporate files, correspondence, and transaction records linked to a long-running effort to move wealth into the United States while keeping the true beneficiaries insulated behind layers of companies and intermediaries.

What the filings do not spell out, and what only became clear through months of cross-referencing corporate records, archived reporting, and court documents across multiple jurisdictions, is who Mahtaub Moore actually is, and what her husband spent two decades quietly building on behalf of one of the Middle East’s most influential ruling families.

The divorce of Jonathon and Mahtaub Moore has now, inadvertently, produced what investigative journalists, congressional researchers, and anti-corruption organisations have sought for years: a documentary window into how the Kurdistan Region’s dominant ruling family — Washington’s ally in the fight against ISIS and a major recipient of American military support — moved well over $100 million into U.S. real estate while keeping their names off the most visible layers of ownership.

The story of how that window opened begins not in Kurdistan, but in the peculiar world of Washington’s political operatives, and with a woman who has operated under at least four different names.

Four Names, One Paper Trail

To understand how a Washington divorce ended up producing such granular claims about the Barzani family’s U.S. footprint, it helps to first understand the person putting the documents into the record. The woman behind the filings has operated in Washington’s political ecosystem for years under multiple names, and her name changes are not a side detail. They are the key to connecting identities that otherwise appear unrelated across public records.

In 2007, a Washington public relations consultant announced the launch of a new Iran-focused think tank, the Institute for Persian Studies, arguing that international backing was needed to accelerate regime change in Tehran. The consultant was quoted publicly as Mattie Fein. Around the same time, reporting identified her as Mahtaub “Mattie” Hojjati, an Iranian-American using the surname of her then-husband, Bruce Fein, a conservative constitutional lawyer and former Reagan Justice Department official. An archived press release from the institute itself used the same linkage, naming its founder as Mahtaub “Mattie” Hojjati.

Those names matter because they are not separate people. They are successive layers of the same biography, scattered across different arenas: political messaging, corporate paperwork, and litigation.

Before the Fein name entered public view, she also appears in court records under Mattie Lolavar. In a 2005 federal lawsuit filed under that name, she described herself as a communications consultant who had been brought into work connected to Ikon Public Affairs, the lobbying firm associated with Roger Stone and Charlie Black, on foreign-related image and political messaging contracts. The case did not ultimately turn on the truth of those allegations, but the filing is revealing for a different reason: it establishes an early pattern of using litigation not only to seek relief, but to surface narratives and documents that put powerful former partners on the defensive.

By 2010, she re-entered the public arena as Mattie Fein, running as a Republican challenger to an entrenched Democratic incumbent in California. She lost, but the campaign further situates her in a world where politics, messaging, and adversarial tactics blur into one another.

The bridge from those earlier identities to Mahtaub Moore runs through court records and a corporate filing that ties her directly to her second marriage. A federal appellate ruling in earlier litigation notes that Lolavar married Bruce Fein in 2004 and changed her name to Mattie Fein. Years later, a biography published under the “Lolavar” name described “Ms. Fein” as the president of a boutique political consulting firm called M22 Strategies, Inc.

That firm is where the story intersects with the divorce that later produced the Barzani-linked filings. Delaware corporate records show M22 Strategies was incorporated on July 30, 2015, and list its registered agent as Jonathon R. Moore, operating out of 1 Wood Road, New Castle, Delaware. When Mahtaub Moore filed her federal complaint in New York on October 3, 2025, she signed it as “mattie moore,” listed her address as 1 Wood Road, Wilmington, and used the email address M22strategies@gmail.com.

Put together, the address, the company name, and the email collapse the distance between identities that, in isolation, look unconnected. Mattie Lolavar, Mahtaub Hojjati, Mattie Fein, and Mahtaub Moore are the same person, and M22 Strategies is the hinge that links her Washington consulting persona to the legal and corporate infrastructure shared with Jonathon Moore.

That continuity matters for the broader Barzani story for two reasons.

First, it helps explain access. The filings are not written like a spouse guessing at hidden wealth from the outside. They read like material produced by someone who understands how corporate entities are layered, how registered agents and mailing addresses can mask beneficial control, and how disclosure can be forced through adversarial process.

Second, it helps explain intent. The divorce is not simply a personal rupture; it becomes a mechanism of exposure. A spouse with experience in Washington’s political and legal ecosystem is unusually well-positioned to turn private records into public leverage. In that sense, the lawsuits are not just about a marriage ending. They are about what happens when the person inside the machinery decides to put the machinery itself on trial.

The Lawyer and His Clients

The divorce filings point repeatedly to one figure at the center of the Barzani brothers’ U.S. footprint: Jonathon R. Moore, a Washington attorney who has practiced since mid-1970s, specializing in corporate law, private client work, and estate planning. His name appears in the record not as a commentator or bystander, but as the legal technician behind the structures that allowed wealth to move quietly, stay compartmentalized, and remain publicly unattributed.

Industry reporting by Intelligence Online identified Moore as a long-time U.S. lawyer for the Barzani family, including Kurdistan Region Prime Minister Masrour Barzani – a relationship that an October 2025 investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and partners later documented in detail.

That investigation reported that the Barzani brothers acquired at least 31 properties across six U.S. states between 2005 and 2019, assembling a real estate portfolio worth more than $100 million. The purchases were executed through offshore entities and U.S. shell companies that obscured the names of the ultimate owners—an architecture consistent with exactly the kind of private-client work Moore has long practiced, and the same kind of entity layering that appears throughout the divorce record.

The question raised by these revelations is not mainly whether the structures were legal on paper; American corporate registries, especially Delaware, are built to facilitate anonymity. The harder question is the provenance of the money.

Masrour Barzani and his brothers have spent their careers inside politics and security. They have no known private business histories that would readily explain nine-figure personal fortunes. They operate within a political economy dominated by oil revenue and state-linked dealmaking, where control over contracts, permits, and exclusive rights can be as valuable as formal salaries. Yet the documented U.S. holdings alone exceed $100 million.

And that figure is conservative: it captures only the properties identified in one investigation, in one country, across a defined window of time.

The Paper Trail

What made the document cache so consequential was not the property list itself, but the internal correspondence that surfaced alongside it, material that Mahtaub Moore’s litigation would later help drag into public view. The emails speak plainly, in private, about arrangements that Kurdish business circles have long treated as open secrets but rarely see recorded with this level of specificity.

Inside the Kurdistan Region, Ster Group is not viewed as just another company. It is widely discussed as a cross-sector conglomerate with deep political proximity, and for years a common claim in business circles has been that it is ultimately owned by Masrour Barzani. That claim has often been hard to prove from the outside because ownership is layered through intermediaries and jurisdictions. The internal materials cited by OCCRP narrowed that gap: they reported that documents show Ster Group is owned by Masrour Barzani, or that he is at least the majority shareholder, and that tens of millions linked to the family’s U.S. property purchases flowed from entities including Ster and other Barzani-linked vehicles.

One email, dated December 2008, captures the mechanics. A tax adviser wrote to Jonathon Moore requesting corporate records for “Masrour Barzani’s overseas company, Ster Group FZE,” including incorporation documents and certificates of “good standing” from the British Virgin Islands for a related entity. Other references in the same set point to signatures, powers of attorney, and the routine paperwork required to connect one corporate vehicle to another. The language is mundane, but the purpose is not. This is what it looks like when control is being formalised while names remain insulated from the most visible layers of ownership.

A similar dynamic appears in the trail around Golden Eagle Global (GEG), a company that operated in the space where government-linked business and private enrichment can overlap. An internal email cited by OCCRP quotes a GEG vice president stating that “a lot of people know that GEG is wholly owned by Mustafa Barzani,” even as formal paperwork suggested otherwise. Another email, from an assistant to Moore in the context of a property purchase, notes that the down payment “will come from family money” and that the relevant documents would arrive from “Iraq.”

The power of these documents is not rhetorical accusation. It is the banality of back-office phrasing: “overseas company,” “common control,” requests for corporate certificates, and quiet references to “family money.” This is language executives and lawyers typically avoid in public and rarely commit to writing unless they believe the audience is limited to insiders.

For the broader story, that is the divorce’s real significance. It does not just produce allegations. It helps force the supporting paperwork into view, turning what “everyone knows” into the kind of record that courts, investigators, and international systems recognise as evidence.

When Households Become Archives

High-conflict divorces do not only divide homes and bank accounts. They divide reputations. When one spouse believes the other’s professional life is the real source of power in the marriage, attacking that professional life becomes an obvious escalation. In this case, Jonathon Moore was not simply a lawyer handling ordinary private-client work. The very role attributed to him in reporting and in the divorce record—designing corporate structures for politically exposed clients—meant that the materials tied to his work could become unusually potent leverage. The more consequential the client, the larger the reputational blast radius.

In marriages, documents travel. They move through shared homes, shared devices, shared storage, shared routines—through the ordinary spillover of work into domestic life. When that domestic life breaks, what was previously protected by habit and trust becomes contested property. Court records summarizing the dispute describe a divorce that escalated into fights over materials retained at the marital home, including proceedings seeking the return of items. In other words, “the papers” were not peripheral to the breakup. They were central.

By October 2025, Mahtaub Moore had shifted that private struggle into a public arena. She filed a sweeping pro se complaint in federal court in New York, framed as a racketeering case, naming Jonathon Moore and Masrour Barzani among the defendants. The complaint mixes personal narrative with financial and national-security allegations. But it is revealing for what it shows about mechanism: she describes access to ledgers and financial records she says were provided to her, claims she reviewed bank flows she believed were suspicious, and portrays the conflict intensifying as she demanded to be removed from certain corporate and trust arrangements.

She also points, in her own filings, to specific repositories of information. In one passage she references a federal subpoena connected to a “Dell server” she describes as abandoned by Moore and in her possession—an example of how a household dispute over devices and boxes can become, in her telling, a dispute over records with far wider implications.

Some of her cases were dismissed or failed on procedural and pleading grounds. The pattern, however, is consistent: she is not only pursuing a private divorce dispute. She is using litigation to force sensitive materials into the open, converting domestic access into public record—and, in the process, turning a marital rupture into an exposure event.

The Spyware Thread

If the real estate structures are about preserving wealth – moving capital into stable jurisdictions and insulating it – interception tools are about leverage and control. They can look like different worlds, but they often run through the same machinery: intermediaries, front entities, and layers designed to keep decision-makers at arm’s length.

In her New York complaint, Mahtaub Moore folds a “cyber-contract” dispute into her wider narrative. She describes being asked to assess “zero-click capabilities,” and claims her husband later sought a refund connected to a Delaware vendor she associates with illegal protocols. Those claims are allegations in a civil filing. But they sit alongside a separate, documented procurement dispute that points in the same direction.

In that dispute, the Barzani side attempted to purchase zero-click spyware through a front company, ASO LLC, run by Afan Omar Sherwani, for a $360,000 contract with a Delaware vendor, HSS Development Group. The technology did not perform as promised, the deal collapsed, and the dispute ended in a confidential settlement. In sworn testimony tied to the case, Sherwani identified his boss as Waysi Barzani and described working on behalf of the Kurdistan government—details that compress the distance between a nominally private contracting vehicle and a political-security hierarchy.

That hierarchy matters. Waysi Barzani is not a distant relative or a peripheral fixer. He is another brother of Masrour Barzani, and he sits at the core of the KDP security apparatus: the head of the Kurdistan Security Council and the figure overseeing the party’s intelligence machinery. In other words, this is not a story about an opportunistic commercial purchase gone wrong; it is a story about an attempted acquisition of intrusion capability that, by the names involved, sits inside the ruling family’s security chain of command.

Moore goes further in her own framing, naming Pegasus and describing an unlawful hacking capability meant to target phones, messaging apps, and email. Those remain allegations. But placed next to the purchase attempt and the wider pattern of offshore-and-shell discipline in the property trail, the through-line is consistent: the same intermediary ecosystem that can quietly move money can also be used to pursue access – whether to assets or to information.

One further detail deepens that picture. Sherwani is not just a random contractor surname in this story. Sherwani is a branch of the Barzani tribal structure, and it is widely understood inside the KDP system that the trusted inner circle around the security apparatus draws heavily from Sherwani and Dolamari sections of the Barzani tribe—alliances treated as dependable precisely because they are tribal as much as institutional.

In the context of this investigation, that is the point. The divorce does not merely air private grievances; it helps pull fragments of a wider operational world – corporate, legal, and technological – into the open, where they can be compared against other records and reporting.

The System

The picture that emerges from the documents, filings, and reporting is not a single scandal. It is a system with three interlocking layers.

The first is the visible political layer in the Kurdistan Region: a ruling family, a dominant party-security apparatus, and a governing structure in which formal institutions, party networks, and economic privilege routinely overlap. This layer concentrates power and generates the resources that need protecting—through oil-linked revenues, state-linked contracts, and exclusive arrangements that can convert public authority into private advantage.

The second is the asset-and-intermediary layer: the offshore entities, U.S. companies, trusts, and property holdings that receive and hold wealth at a distance. This is the domain of legal and administrative engineering—registered agents, nominee structures, paperwork trails that connect one vehicle to another while keeping the most sensitive names away from the most visible layers of ownership. This is where the property records and internal correspondence provide the hard map.

The third is the rupture layer: the personal trust that allows the first two to function quietly. This is the layer that failed when the Moore marriage collapsed. A divorce that began as a private dispute became a fight over documents and devices, and that fight widened the aperture enough for parts of a much larger documentary ecosystem to spill into public view—alongside side-threads, like the attempted procurement of interception tools, that sit in the same intermediary universe.

That is why this story matters. It reverses the usual direction of accountability. Power normally protects itself from the center outward, behind discipline, privilege, and silence. Here, the pressure came from the edge: a domestic breakdown turned a household into an archive, and an archive into a public record. In systems built on secrecy, the weakest point is rarely the paperwork. It is the human trust that keeps the paperwork contained.

What Remains

The Barzani family’s American footprint was engineered for silence—quiet enough to weather political turbulence in Iraq, opaque enough to deflect scrutiny in Washington, and structured to resemble routine asset management rather than the offshore parking of political wealth.

It took a domestic rupture in Delaware to make it loud. The exposure did not come because the American system suddenly embraced transparency, but because human conflict has a way of dragging paper out of the drawer and into the court file.

In the months ahead, much will remain contested. Courts may dismiss parts of the litigation on procedural grounds without ever reaching the merits. The spyware thread may remain partially obscured if key records stay sealed or commercial settlements keep the underlying detail out of view.

But the documentary record has shifted. A private email identifying Ster Group as Masrour Barzani’s overseas company is no longer a rumor; it is the kind of internal shorthand people use only when they believe no one is watching. A corporate officer writing that “a lot of people know” a U.S. contractor is “wholly owned by a Barzani” captures the social reality of ownership even when paperwork denies it. And a deposition in which an operator identifies his boss as a Barzani and says he worked for the KRG collapses the carefully maintained distinction between private corporate procurement and state-aligned intent.

In the Kurdistan Region, people have always argued about what the Barzanis own. Now, because two people stopped protecting each other, the argument has moved onto paper.

Mahtaub Moore may be motivated by vengeance, by a genuine sense of exploitation, by ideological conviction, or by some combination of all three. But a woman who has spent decades navigating Washington’s information economy – shifting names and roles across think tanks, campaigns, and consulting work – understood exactly what she was holding when those files landed in her possession.

Whether she is seen as a whistleblower, an opportunist, or something more complicated, the outcome is the same: the documents she accessed have outlasted every motion to dismiss.

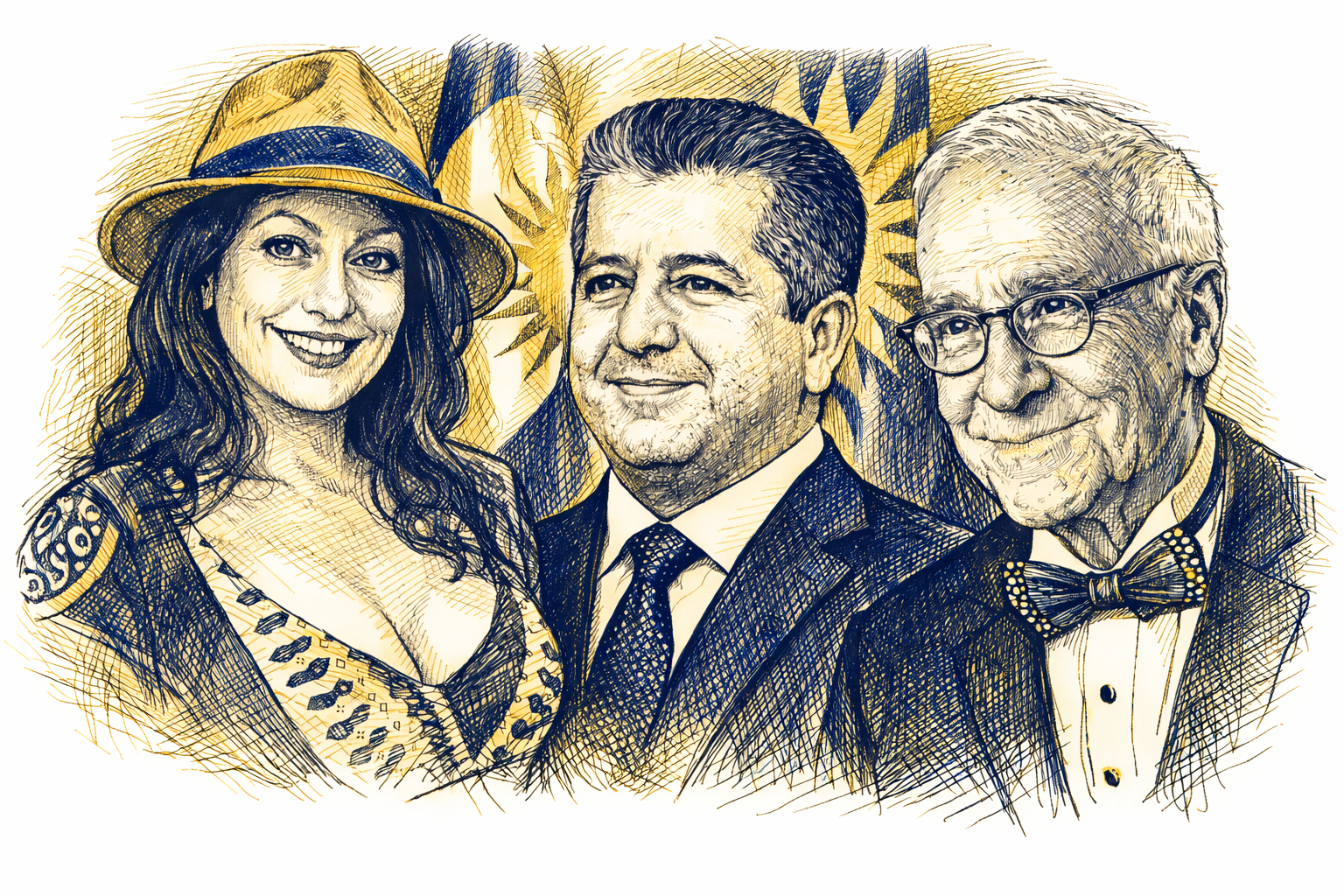

Editor’s note: This report has been updated to include a more recent photo of Mahtaub Moore.