Damascus Tests the SDF With a “Three Divisions” Offer

The Syrian government and the SDF are accelerating talks ahead of the end-of-2025 deadline set out in the March 10 Damascus–SDF agreement, but the chances of a last-minute, full integration deal remain low. Reuters reports that Damascus has sent the SDF a proposal that would allow the force to reorganise roughly 50,000 fighters into three main divisions plus smaller brigades. The offer, as described by multiple officials, comes with two core conditions: the SDF must cede parts of its command chain and open SDF-held territory to other Syrian army units.

Context: The March 10 agreement committed both sides to merge northeastern Syria’s civil and military institutions into the Syrian state by year-end 2025, but it left crucial mechanics unresolved, including the shape of command, deployment, and what “integration” would mean in practice. The “three divisions” concept is not new. The SDF floated a version of it earlier, including in comments by SDF commander Mazloum Abdi, and the latest Damascus proposal appears to be an effort to translate that idea into a state-led framework with explicit conditions attached.

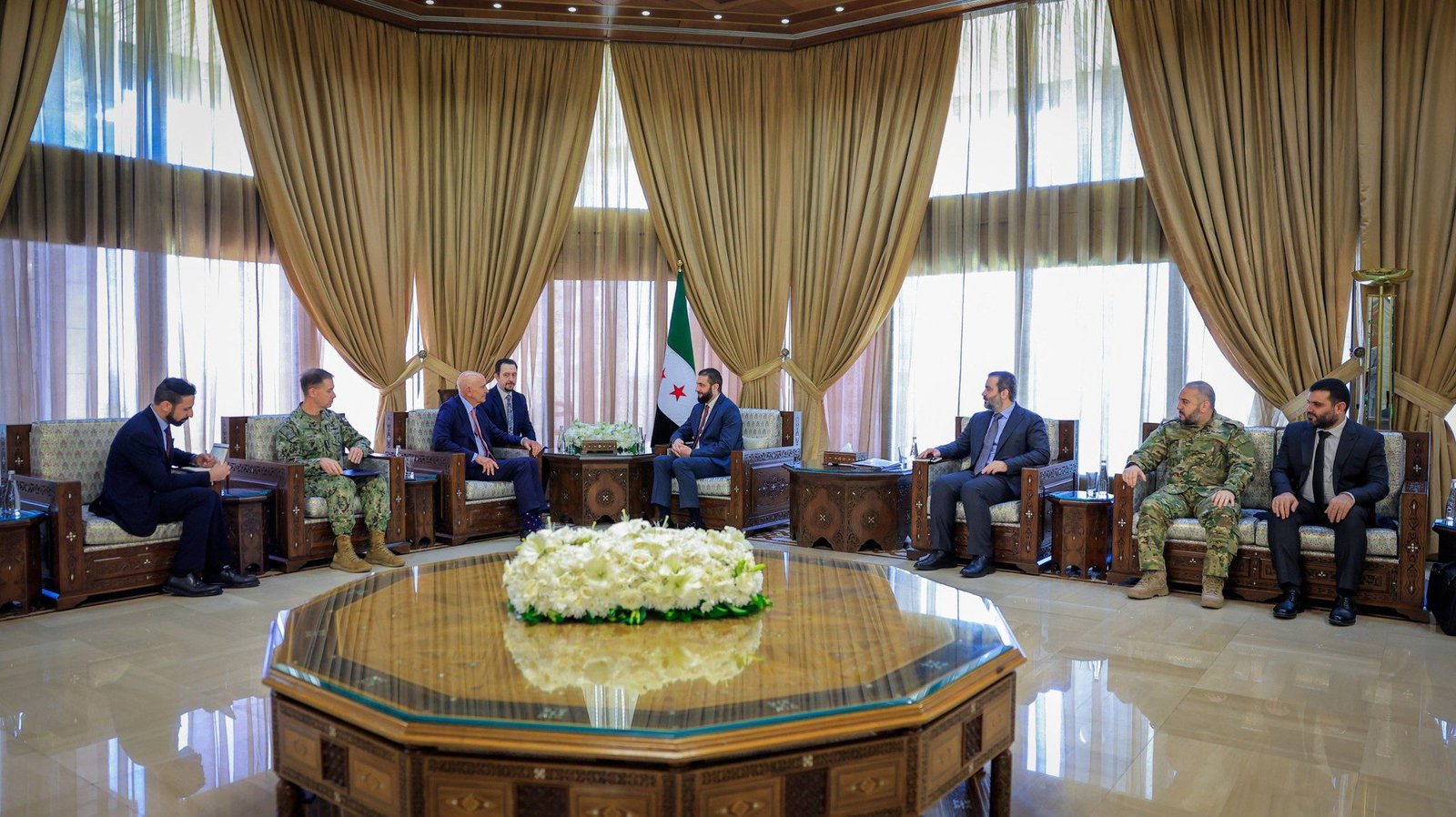

Analysis: Despite heightened rumours of an imminent breakthrough, the current proposals still point to an agreement that is unlikely to close in full before the deadline. The more realistic objective, and one the United States appears to be pushing for, is modest: a set of initial, face-saving steps that can justify extending the March 10 deadline. Neither side wants a war at this stage, but neither can afford to show it made major concessions either. For now, much of what is circulating still sits in the realm of proposals, managed leaks, and trial balloons, rather than any agreement.

The clash is structural. The SDF has favoured integration as a cohesive force, while Damascus has leaned toward absorption as individuals. The updated Damascus formula tries to look like a compromise by accepting the SDF’s preferred optics, three divisions inside the army structure, while demanding the substance Damascus cares about, partial surrender of command authority and the end of exclusive territorial control through the entry and movement of other Syrian units.

The SDF might accept a symbolic Syrian army presence in limited areas, similar to the old “security square” model under the previous regime, but Damascus is unlikely to accept an arrangement that keeps the SDF’s exclusive control of the broader territory intact. That helps explain why even seemingly expansive packages fail to produce movement. Some accounts suggest the SDF has been offered incorporation as three divisions, expanded Kurdish civil rights, ministerial roles, and senior placements for commanders inside defence and interior institutions, yet there is still no agreement. The reason is simple: the dispute is not about symbolism but about coercive power and credible guarantees. Damascus’s condition about opening territory to other Syrian units goes straight at what matters most to any autonomous force: exclusive control of the ground.

Seen this way, the Damascus proposal also functions as a tactical move. By putting forward a headline-friendly “three divisions” offer while attaching conditions the SDF is unlikely to accept, Damascus can shift the burden of refusal onto the SDF, especially with Washington acting as the key tempo-setter. It also plays into the social geography of the SDF-held northeast. If non-SDF Syrian units enter predominantly Arab areas, Damascus may calculate that local grievances and anti-SDF mobilisation could intensify and further weaken the SDF’s negotiating position. On the command question, Damascus may also be betting that because a large share of SDF fighters are Arab, shifting payroll and chain-of-command gravity toward the state could hollow out the SDF’s cohesion over time, leaving a smaller Kurdish core with less leverage. The SDF understands these dynamics, which is why it is unlikely to accept an arrangement that dilutes exclusive control without ironclad guarantees.

For now, the overriding goal is to postpone war, not to consummate integration. The integration track is tied to ISIS detention and the wider counter-ISIS architecture. A Damascus–SDF clash would risk destabilising prisons and camps, create openings for ISIS cells, and raise the likelihood of Turkish military intervention. Reuters’ depiction of U.S. facilitation fits this logic: Washington’s priority is to keep the anti-ISIS system intact while nudging both sides toward incremental, reversible steps that reduce the temperature.

Both sides are also playing for time, but with different endgames. For al-Sharaa, the logic is to consolidate power, deepen security cooperation with the United States, especially on counter-ISIS operations, and gradually reduce the SDF’s leverage. With the Caesar Act now repealed and signed into law on 18 December 2025, Damascus is betting that the biggest legal deterrent to serious reconstruction finance and external investment has eased, enabling at least a modest economic uptick that can translate into local pressure on the SDF as communities demand jobs, services, and access to markets. The SDF, meanwhile, also benefits from time, because prolonged stalemate can harden into de facto acceptance of its rule.

The risks are real on both sides. Economic momentum may stall if investors perceive that war remains plausible due to unresolved files, including the SDF question and the Druze question. For the SDF, the overriding risk is a shift toward military options, especially if Turkey’s alignment with Washington deepens. Reports that Ankara may be willing to part with the S-400 issue by returning the system to Russia would further widen the space for U.S.-Turkish understandings and could increase the likelihood that Washington tolerates limited Turkish action if talks drag on. For now, war remains a postponed prospect, but whether it stays postponed will hinge on U.S.-Turkish, and by extension Israeli, understandings, because a military operation against the SDF is fundamentally a political decision.