Baghdad Splits the KRG Oil File: Khurmala Separated from IOC Demands

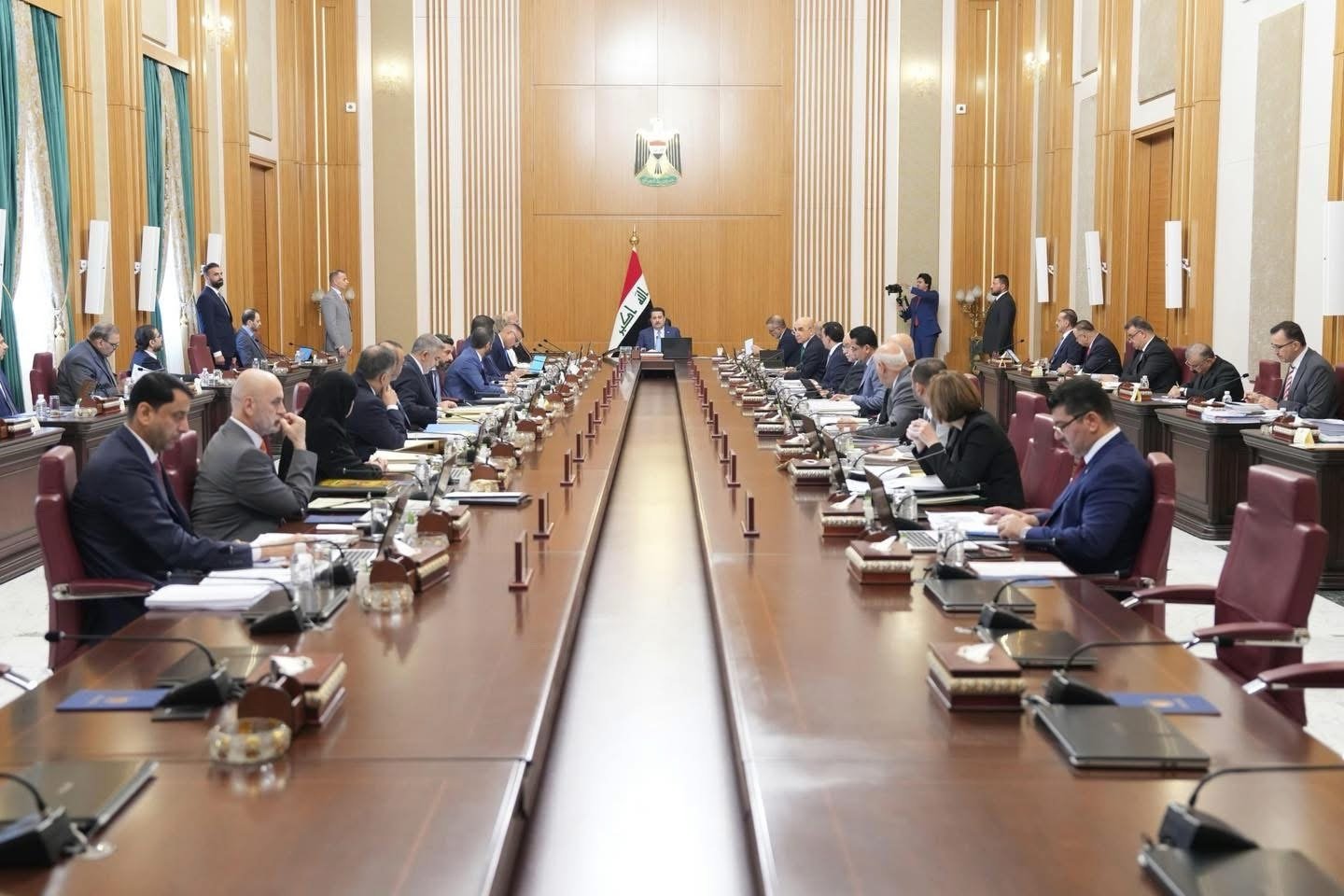

At its meeting today, Iraq’s Council of Ministers declined the KRG’s proposal on both oil and non-oil revenues. On non-oil revenues, the cabinet referred the dispute to the Council of State (Majlis al-Dawla) for a legal opinion. On oil, it ruled that crude produced by local companies in the Kurdistan Region should be handled separately: 50,000 barrels per day to remain for local consumption inside the KRG, with the remainder handed to the federal government to decide whether for domestic use or export.

Context: The decision to send the non-oil revenue file to the Council of State is significant because the body issues only consultative opinions, not binding rulings. This means the dispute will likely drag on. The KRG, by contrast, had hoped the matter would go directly to the Federal Supreme Court, where a binding ruling would have provided clarity and accelerated the process.

On oil, the reference to “local companies” essentially points to KAR Group, which operates the Khurmala oil field, producing more than 100,000 barrels per day—around 40 percent of the KRG’s total output. By carving out this case, Baghdad is drawing a distinction between oil produced by domestic operators and oil produced by international oil companies (IOCs) under production-sharing contracts.

Analysis: On oil. Baghdad’s decision marks an important shift: it is now separating local-company oil from IOC oil. With Khurmala/KAR Group, the contract history is unique. Unlike the KRG’s production-sharing agreements with IOCs, the Khurmala arrangement was originally a service-based contract signed with Baghdad during Nechirvan Barzani’s government, during Nouri al-Maliki’s tenure with late Iraqi President Jalal Talabani involved. Under this structure, KAR Group only has a share in production, not full rights to the field.

This distinction gives Baghdad stronger legal ground. Politically, it also matters because Khurmala is located in disputed territory near Makhmur, straddling Erbil and Nineveh governorates, beyond the old 36th parallel line. Baghdad views this as its own oil field, making the move as much about asserting federal control as about production numbers. If 50,000 barrels are retained for KRG consumption and the rest handed to Baghdad, the likely outcome is that these barrels will be used for domestic refining inside Iraq, not export. This is less about volumes and more about precedent and leverage.

By contrast, the IOC-operated fields remain in limbo. Their contracts are production-sharing agreements, legally and politically more complicated. IOCs are demanding written federal guarantees and even international arbitration clauses in any new arrangement. According to Kurdish MP Ali Hama Saleh, companies want disputes to be settled in international courts. Baghdad flatly rejects this, insisting Iraq’s oil is a matter of sovereign jurisdiction that must remain under domestic law. In practice, this suggests Baghdad is in no rush to bring IOC barrels back online under current terms.

On non-oil revenues, the KRG’s rejected proposal reportedly offered to remit 50 percent of a defined set of federal-type revenues—such as customs, federal income tax, and fees or stamp duties tied to federal services delivered in the region (for example, through the Ministries of Labour or Natural Resources). This set covered roughly eleven revenue streams. For the much larger group of KRG-specific revenues—around sixty streams, including electricity tariffs, environmental and investment fees, municipality income, and items overseen by the Ministry of Natural Resources—the KRG proposed to retain 100 percent. Baghdad’s position, by contrast, is that all revenues should be remitted in full to the federal treasury, with 50 percent then returned to the KRG. By sending the matter to the Council of State, the cabinet has chosen a slower, advisory route that is unlikely to produce a quick, binding outcome.

Taken together, Baghdad’s decisions reveal a deliberate strategy: carve out a controllable, low-risk slice of the oil file while deferring non-oil revenues to a drawn-out legal process. This approach strengthens Baghdad’s leverage without requiring immediate political concessions. For the KRG, however, the consequences are mounting, salary arrears are deepening, and the fiscal squeeze is growing more severe.