Turkey Locks In “Oil-for-Water” Mechanism With Iraq as Ankara Expands Regional Leverage

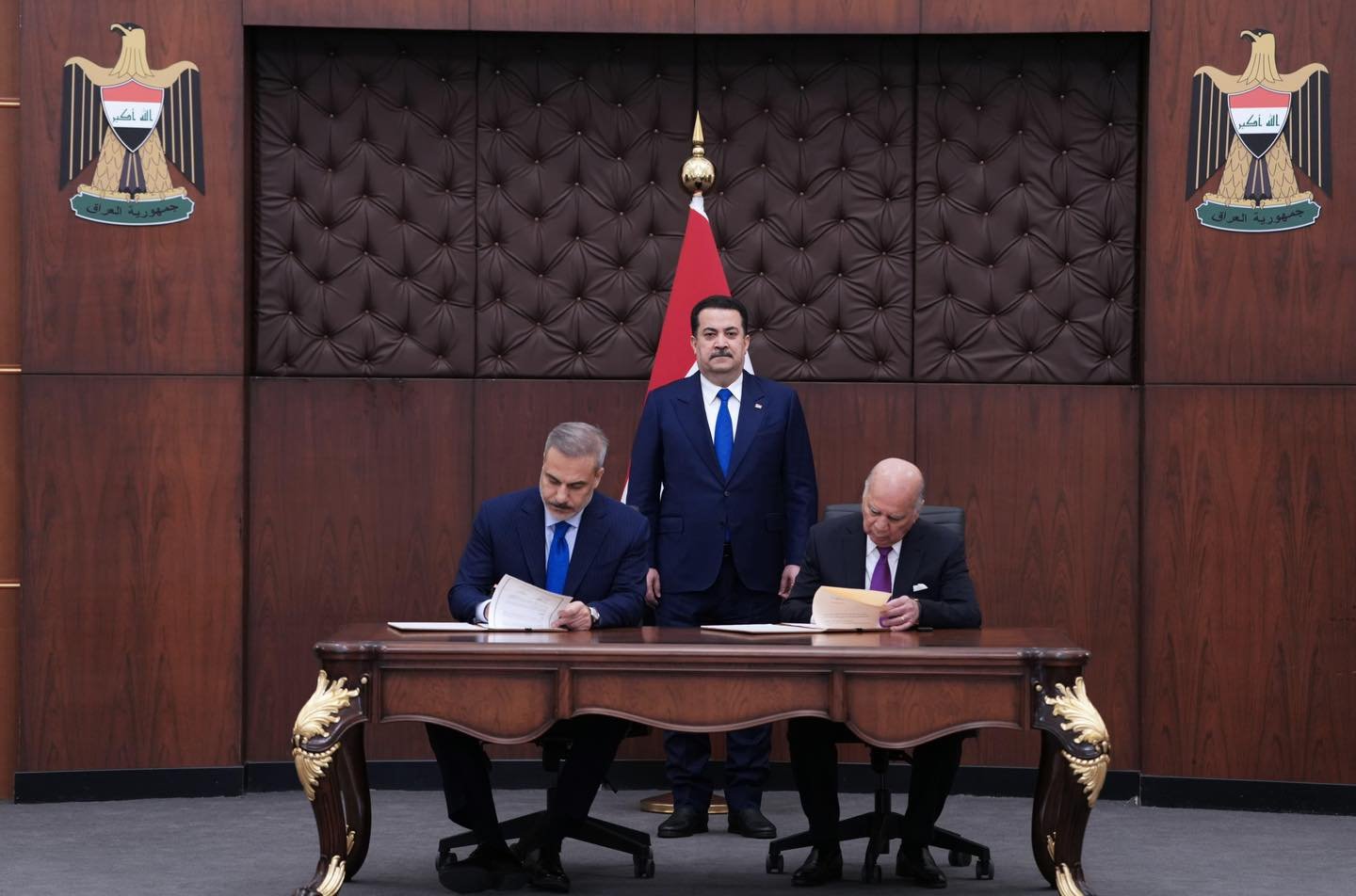

The Iraqi Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein and Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan signed an executive financing and implementation mechanism for water cooperation, witnessed by Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani. The mechanism channels Iraqi oil-sale revenues to Turkey to pay Turkish firms to deliver water projects inside Iraq. Officials announced an initial tranche including three water-harvesting dams and three land-reclamation schemes, though no fixed flow quotas were published.

Context: Today’s document operationalizes the framework agreed during President Erdoğan’s 2024 visit to Baghdad – it establishes funding pathways and tender rules, not a new water-sharing treaty. Baghdad will form a committee to tender projects to Turkish companies; Ankara frames the arrangement as making Iraq’s water use “effective, productive and sustainable,” though both sides left volumes and allocations unspecified. The signing sits alongside broader bilateral files and security cooperation against the PKK and new connectivity corridors but on water this is a follow-up implementation step, not a quota deal.

Analysis: The Iraqi side appears to be overstating the agreement’s scope. With elections looming, Baghdad wants to claim it has solved the water crisis, a genuinely severe problem as the Tigris has dried up or come close in recent seasons. Even the document’s title reads like a cooperation framework on infrastructure mechanisms rather than a final settlement. A definitive treaty remains unlikely because the two countries’ positions are fundamentally incompatible. Iraq has signed the UN Convention on International Watercourses and insists the Tigris is an international river to be shared equitably. Turkey has not signed and rejects that premise, arguing the Tigris is a Turkish river that crosses a border. Iraq gets what it can negotiate with Ankara.

What today’s mechanism actually does is shift leverage. It is effectively an “oil-for-water” arrangement that increases Turkish control and influence. Turkish companies will overhaul Iraq’s water management, with funding tied to Iraqi oil sales to Turkey. As the stronger party, Turkey can steer Iraq toward the Turkish approach: Turkish firms enter Iraq, build reservoirs, dams, and drought-mitigation systems, and Turkey modestly increases Iraq’s water allocation. But the additional flow is managed to prevent evaporation or waste, using the scientific methods Ankara prefers, so Iraq genuinely benefits.

This agreement should be understood within the wider realignment underway since President Erdoğan’s visit last year, when more than two dozen agreements and MOUs were signed. Turkey is gradually pulling Iraq somewhat out from under Iran’s influence and opening the door to greater Turkish involvement. The contours are becoming visible. First, Iraq will assist Turkey on security, treating PKK members who fled across the border as threats rather than political refugees and preventing them from rearming. Second, Turkey will help Iraq on water, but on Turkish terms and according to Ankara’s management model. Third, and perhaps most strategically, more Iraqi oil will be exported through Turkey, bringing Ankara revenue and securing oil supplies instead of relying on Russian imports, a shift Washington has quietly encouraged. There is also agreement on the new overland trade corridor running from Basra port north to Turkey, a major infrastructure project designed to tie Iraq more tightly to Turkey and reduce Baghdad’s dependence on Tehran within this broader framework.