Peace with PKK, Crackdown on CHP: The AKP-MHP Strategy to Rule Past 2028

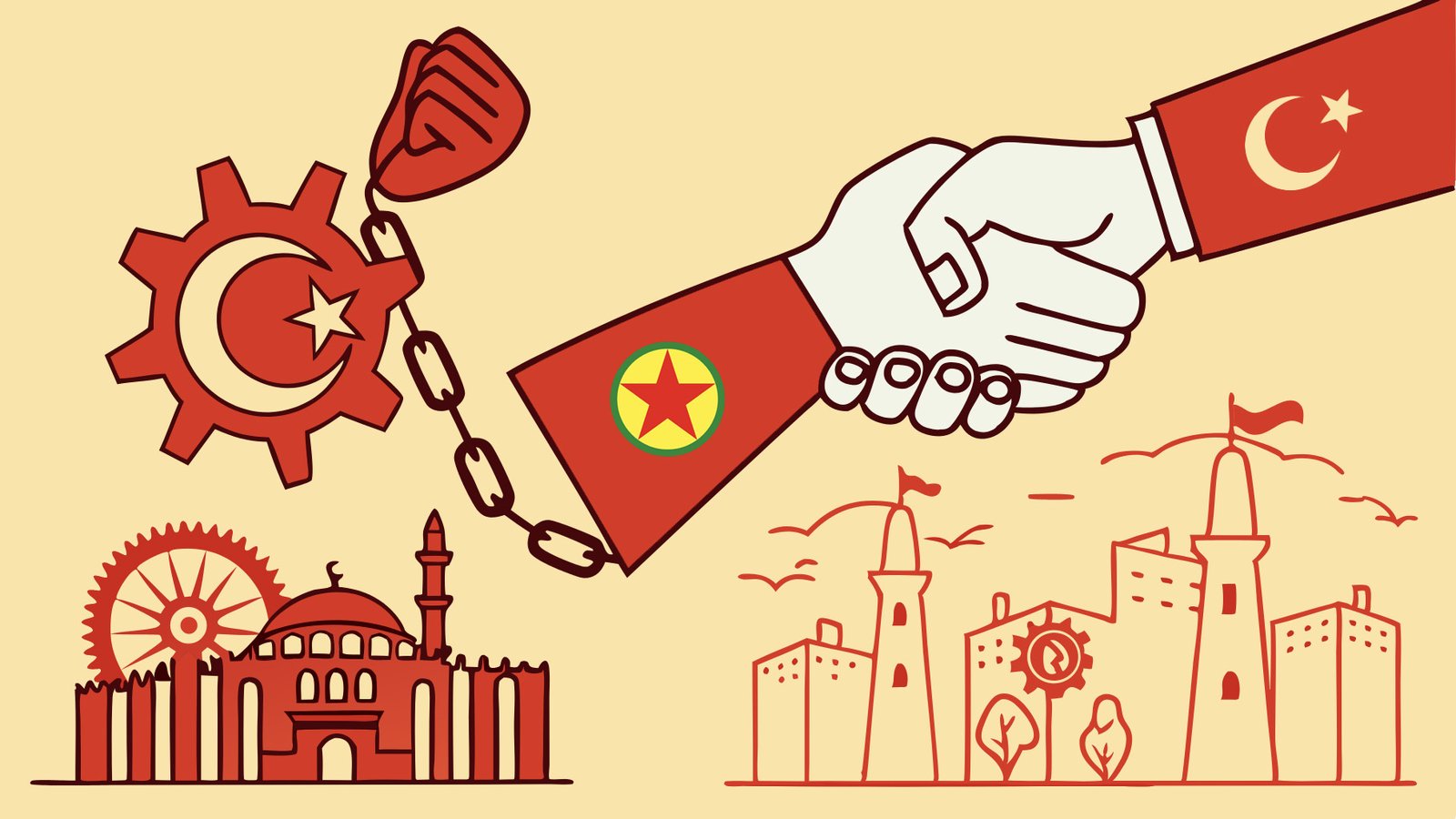

Yesterday’s arrest of the popular opposition Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu appears contradictory when viewed through the lens of recent peace talks with the PKK and its leader Öcalan—talks that emphasize “democratization” as the remedy for the Kurdish issue. Yet we’re witnessing the opposite unfold. What seems particularly paradoxical is that among the key charges against İmamoğlu is collaboration with “terror groups” or individuals affiliated with the PKK—the very organization with which the Turkish state is simultaneously negotiating.

For close observers of Turkish politics, this contradiction is neither surprising nor unexpected. The Turkish government has initiated a sweeping crackdown on opposition forces in recent weeks, concurrent with its negotiations with Öcalan. Analyzing these developments reveals a clear strategy being implemented jointly by Erdoğan and Bahçeli:

After the new year, coinciding with Trump’s inauguration in the United States and Bahçeli’s calls for peace talks with the PKK to resolve the Kurdish issue, the Turkish government launched a series of repressive measures against opposition figures. The campaign began with the arrest of far-right opposition figure Ümit Özdağ on January 20th and has since expanded to include numerous detentions, including a senior official from Turkey’s main business association TÜSIAD in February, who had criticized the judicial crackdown on opposition leaders and journalists. This systematic suppression of dissent has been steadily intensifying since early 2025. Simultaneously, on February 27th, Öcalan urged the PKK to disarm and engage in Turkish politics through peaceful means, emphasizing that democratization in Turkey is the solution to the Kurdish issue.

Understanding this strategy requires considering the instrumental role played by pro-Kurdish parties, notably HDP and its successor, DEM Party, within Turkey’s broader opposition coalition:

The pro-Kurdish HDP (now DEM Party) has become a crucial ally of the CHP and the broader opposition in recent years. This alliance enabled opposition victories in key metropolitan centers like Istanbul and Ankara in 2019, catalyzing a significant revival of opposition forces and the emergence of new leaders capable of challenging Erdoğan and the ruling coalition. For Erdoğan, opposition is tolerable as long as it doesn’t threaten his grip on power, but this new dynamic of Kurdish-mainstream opposition cooperation was gradually creating conditions that could lead to his political downfall.

It’s worth recalling that Erdoğan engaged in negotiations with Kurdish representatives and the PKK from approximately 2009 to 2014. However, when his hold on power appeared threatened, he pivoted strategically and by 2016 had forged a new alliance with the ultra-nationalist MHP. Since then, MHP leader Bahçeli has become an instrumental figure in the Turkish state apparatus. Ironically, the MHP has been more aggressive than Erdoğan’s AKP in advocating for increased state securitization and curtailment of civil liberties. For instance, Bahçeli, more so than Erdoğan, has consistently criticized the courts—particularly the Constitutional Court—for rulings deemed too liberal.

When considering potential coalition partners to broaden their base, the AKP-MHP alliance faced limited options. The CHP represents AKP’s direct rival seeking to unseat Erdoğan, making collaboration politically unfeasible. Similarly, an alliance with the nationalist İYİ Party would necessitate abandoning the MHP partnership, as İYİ is MHP’s principal competitor. This leaves the Kurdish bloc—despite being labeled as “terrorists” until recently—as the only viable major faction that could be integrated into the governing coalition without threatening its existing power structure. Moreover, the regional geopolitical changes have further made this option feasible.

The current situation reflects the reality that Erdoğan and Bahçeli can no longer govern independently as their popular support continues to erode, leaving them without sufficient numbers to restructure the state for their next phase of governance. Importantly, this restructuring transcends domestic Turkish politics; the objective is to reconfigure the state in a manner that provides more ambitious mechanisms to position Turkey as a formidable regional power.

The peace negotiations with Öcalan have effectively neutralized the DEM Party, enabling the Erdoğan-Bahçeli alliance to target Erdoğan’s direct rival, İmamoğlu. This explains the conspicuous silence from the DEM Party regarding İmamoğlu’s arrest. Even Selahattin Demirtaş—the architect of the Kurdish pivot toward the CHP and historically one of Erdoğan’s most vocal critics—has recently commended Erdoğan and Bahçeli for their negotiations with Öcalan and has remained notably silent on İmamoğlu’s detention. A year or two ago, he would have immediately issued a forceful statement via Twitter.

Beyond domestic considerations, robust regional and global factors are emboldening Erdoğan’s assertive maneuvers. Trump’s return to power has likely diminished Erdoğan’s concerns about international repercussions for his suppression of opposition voices. Trump has repeatedly expressed admiration for Erdoğan’s governance approach, suggesting tacit approval of these authoritarian measures. Concurrently, Europe finds itself in a vulnerable position, preoccupied with the Ukraine conflict and increasingly at odds with Trump, rendering them more dependent on Turkey given its military manpower and defense industry. This dependency makes substantive European responses less probable. This explains why we’ve only observed symbolic statements from the EU without concrete actions. In previous years, such developments might have triggered sanctions against Turkey and the judiciary involved in these proceedings.

Additionally, regional tensions—including the Gaza conflict, potential military actions against the Houthis and Iran, and ongoing instability in Syria—have diverted international attention away from Turkey’s internal affairs, creating a window of opportunity for Erdoğan to consolidate power without significant external scrutiny.

The emerging strategy aims to broaden Erdoğan’s coalition to extend his rule beyond 2028, incorporating Kurdish support while systematically excluding other groups. While the current international and regional climate creates favorable conditions for Erdoğan to implement divisive measures to marginalize his primary challengers and consolidate power, this occurs at a time when the CHP—particularly İmamoğlu—enjoys unprecedented popularity. The CHP secured more votes than the AKP in last year’s local elections, with İmamoğlu winning Istanbul by an 11.6% margin over the AKP candidate. In Ankara, the CHP achieved a remarkable 29% victory margin, and nationwide, the CHP garnered nearly two million more votes than the AKP. If Erdoğan’s plan is viewed within this framework, he will likely attempt to neutralize and clamp down on the Ankara mayor Mansur Yavaş as well.

Although the next presidential election isn’t until 2028, current circumstances provide Erdoğan with an optimal opportunity to advance his agenda, both for the reasons mentioned and because under the current constitutional framework, he is ineligible to seek another presidential term. However, part of the arrangement with Öcalan involves constitutional change that would likely reset Erdoğan’s term limits.

The underlying objective likely transcends Erdoğan’s personal ambition to retain the presidency, considering he now leads an expanding coalition of diverse factions. Figures like Bahçeli pursue distinct objectives and aren’t merely supporting Erdoğan’s personal aspirations. Even within the judiciary, they are not simply Erdoğan’s subordinates but represent various elements of this broad coalition. This dynamic was evident in, for example, the election of the president of the Court of Cassation last year, which required 37 rounds of voting due to competing factions within the judiciary. Notably, Erdoğan supported the incumbent Mehmet Akarca, who ultimately lost to Ömer Kerkez—a candidate backed by a diverse alliance including the Menzil religious sect, nationalist groups, and even elements within the CHP.

With Kurdish integration into this growing coalition—if the Öcalan-Bahçeli deal bears fruit—Erdoğan will increasingly need to accommodate the demands of competing factions. What appears to be emerging resembles an Ottoman-style governance system—with a Sultan-like figure serving as the unifying authority, beneath whom various factions vie for influence and resources. This system will likely feature fewer democratic elements politically while expanding cultural freedoms within a civilizational understanding of the state that accommodates Kurdish identity. This parallel becomes increasingly apt as Turkey evolves into a regional powerhouse with expansive multi-regional ambitions. For instance, the Kurds can be useful for Turkey’s expansive regional ambitions in the Middle East given the large Kurdish population in the southern borders of Turkey, while nationalists can facilitate expanding ties into Central Asia. This transformation is occurring in tandem with major geopolitical shifts globally that appear to be reversing the post-Cold War order toward a multipolar configuration resembling the pre-1920s international system. Turkey’s recalibration of its governance structure and regional posture can be seen as part of this broader historical realignment. However, given the significant challenges confronting this strategy, both domestically and internationally, its ultimate viability remains uncertain.