Halabja’s Governorate Status Triggers Battle to Redraw Iraq’s Map

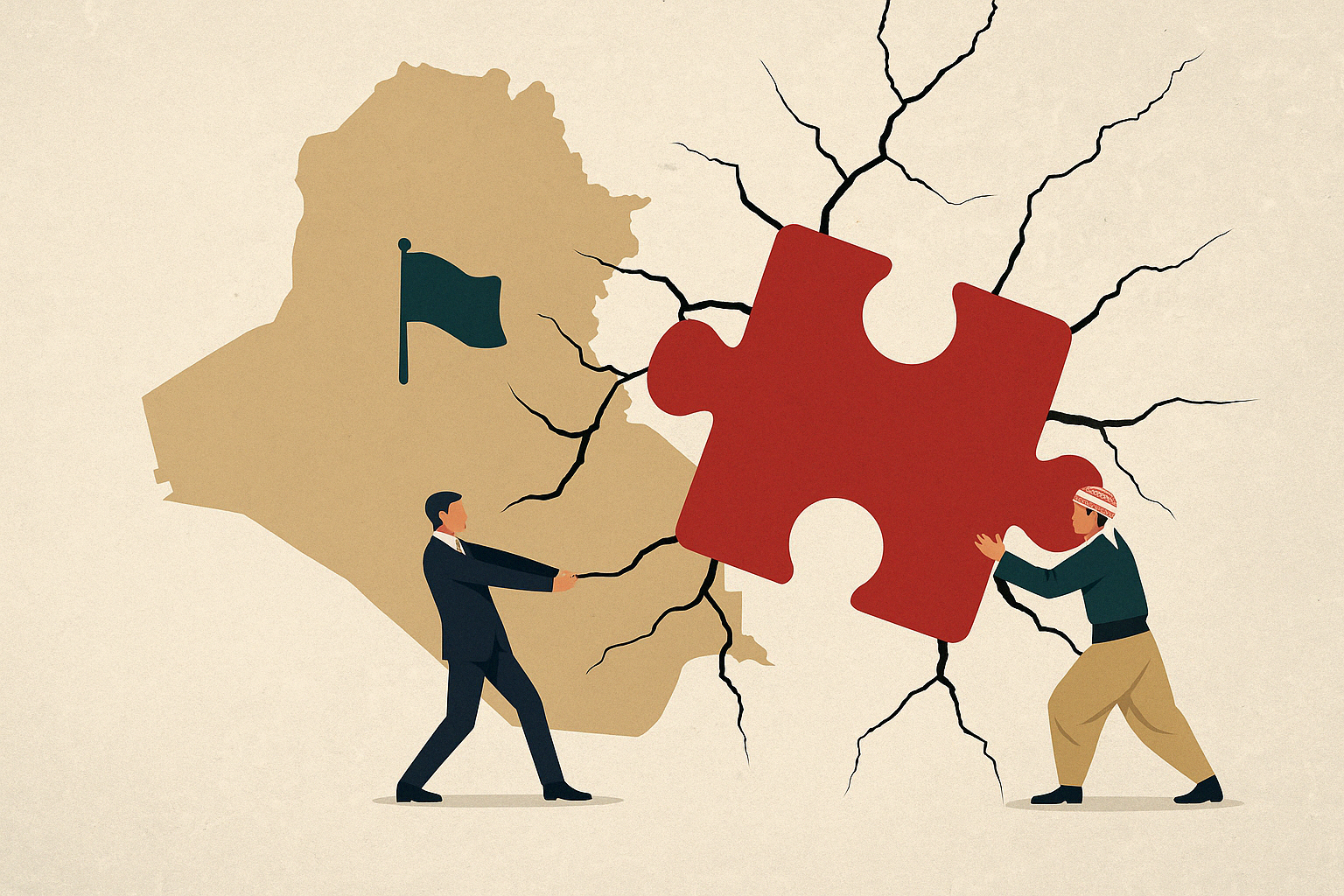

The Iraqi Parliament’s vote on April 14, 2025, to officially recognize Halabja as the country’s 19th province has triggered a cascade of renewed demands to redraw the administrative map—many of which had stalled for years. The move marks the first successful alteration to Iraq’s governorate structure since the Ba’athist era. Now, momentum is building behind at least four additional proposals, each backed by competing factions seeking local power, national leverage, or sectarian insulation. If realized, these demands would increase Iraq’s provinces from 19 to at least 23.

The most ambitious proposal comes from the Badr bloc, which is pushing for a new province in Nineveh encompassing the Nineveh Plains, Tal Afar, and Sinjar. The plan brings together Iraq’s most politically sensitive minority areas: the Nineveh Plains, home to Iraq’s Christian communities (primarily Chaldeans, Assyrians, and Syriacs); Tal Afar, with its large Turkmen population; and Sinjar, the historical heartland of the Yazidis. Badr frames the initiative as a corrective to the marginalization of Iraq’s minority components. But it is unclear whether these communities support the idea. Christians, Yazidis, and Turkmen have each historically demanded separate provinces of their own—often precisely to avoid being grouped with other communities under a shared administrative umbrella.

The proposal has already drawn sharp opposition from Sunni parties. Former Speaker Osama al-Nujaifi’s Mutahidun Party warned that the plan would fragment Nineveh along sectarian and ethnic lines. The Azm Alliance voiced similar concerns. In contrast, Waad Qaddo, a Shabak MP from Nineveh who is politically aligned with the Badr Organization, defended the proposal. He argued that areas like Sinjar, Tal Afar, and the Nineveh Plains have been systematically marginalized by successive provincial administrations—and that a new governorate is necessary to correct that imbalance.

Beyond community-level sensitivities, the proposal carries deeper political stakes. Many see it as a strategic effort by pro-Iran Shia factions to consolidate influence in northern Iraq. The Babylon Movement, which now dominates Christian representation in the Nineveh Plains, is closely aligned with Shia political factions. Similarly, Shia Turkmen, who have a strong presence in Tal Afar, and Shabak politicians in the Nineveh Plains—many of whom lean toward Iran—are part of the demographic makeup that makes such a governorate attractive to pro-Iran factions.

A new administrative unit covering these areas could serve as a launching pad for Shia-aligned forces deep inside Iraq’s Sunni-Kurdish northern heartland, particularly across disputed territories between Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government. In this sense, the project is not merely administrative—it could reconfigure the balance of power across one of Iraq’s most strategically sensitive frontlines.

This also has ramifications beyond Iraq’s internal politics. For instance, Qais al-Khazali recently claimed that Turkey is attempting to assert control over northern Iraq, including Mosul and Kirkuk, as part of a broader regional strategy that began in Syria, following the collapse of the Assad regime and the rise of a new Turkey-friendly government in Damascus.

It remains unclear whether the vote on Halabja’s governorate status was part of a quid pro quo, but Shia factions—now that the door to creating new provinces is open—are moving to carve out new governorates in the north aligned with their interests. This is also a pushback, given the strategic and symbolic importance of northern Iraq, which was historically part of the Mosul Vilayet under the Ottoman Empire.

Turkey renounced its claim to the region in 1926, during negotiations with the British over what became known as the Mosul Question, which ultimately secured the area for the newly created Iraqi state. But since then, Ankara has continually sought to reclaim influence in this historically contested zone—making today’s governorate politics part of a much broader geopolitical contest.

The Nineveh proposal is not the only map in play. In Salah al-Din, Turkmen political actors are reviving calls to establish Tuz Khurmatu as a separate governorate. The district’s Shia Turkmen community is now politically dominant, with many aligned to the Badr Organization, a leading pro-Iran Shia faction. While Sunni Arabs and Kurds also reside in the area, the most recent local post-distribution saw Turkmen, mostly Shia, claim 65% of administrative positions, compared to 25% for Sunni Arabs and 10% for Kurds. These shares reflect political power more than exact demographic proportions, but they illustrate the sectarian tilt behind the governorate push. Any redrawing of Tuz Khurmatu’s status risks entrenching that dominance under the banner of administrative reform.

Just as with the Nineveh proposal, the creation of a Tuz Khurmatu governorate would further embed new centers of power for pro-Iran Shia factions in a part of Iraq historically dominated by Kurdish and Sunni political forces. It would shift the balance in a strategically sensitive corridor and deepen the fragmentation of territories still contested between Baghdad and the KRG.

In Salah al-Din, pressure is again mounting to separate Samarra into its own province. The district is Sunni-majority but demographically mixed due to the presence of the al-Askari shrine, one of the holiest sites in Shia Islam. That dual identity gives Samarra both symbolic weight and political sensitivity. Its administrative fate remains a point of quiet contestation between Shia power centers and Sunni local leadership.

In the far south, the proposed creation of a Zubair province—currently part of Basra—has less to do with identity politics and more with internal Shia rivalries. Zubair is a strategic district, home to significant oil infrastructure. Pushing it toward provincial status is widely seen as a move to weaken Basra Governor As’ad al-Edani, who has built a stronghold in the province. Shia factions in Baghdad view redrawing Basra’s map as a means to dilute his influence and redistribute local authority.

What’s unfolding is not just an administrative reshuffle. It is a quiet, high-stakes battle over territorial influence, local autonomy, and the sectarian architecture of post-2003 Iraq. With no clear institutional barriers in place, the political precedent set by Halabja may prove more important than any legal principle.