Written by

Explained: Understanding the Civil Servant Protests in Kurdistan’s Sulaimani

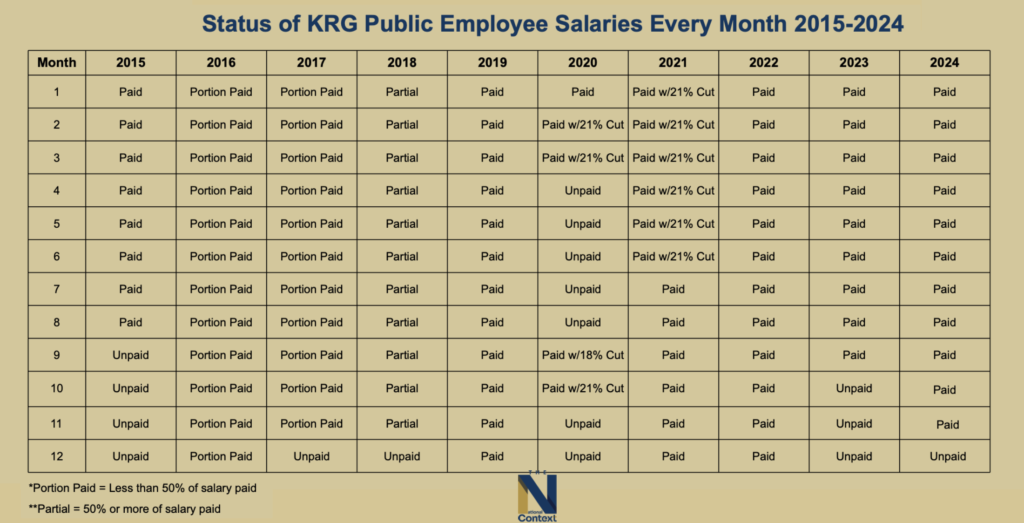

For over 12 days, civil servants in the Kurdistan Region’s Sulaimani province have been staging protests. Among them, 12 have embarked on a hunger strike. Today, hundreds of demonstrators attempted to march toward Erbil to demand a permanent resolution to the ongoing salary crisis. However, they were stopped at the notorious Degala checkpoint, which marks the division between the de facto zones controlled by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK).

The salary crisis in the Kurdistan Region traces back to 2014, when a dispute over natural resource management escalated. The KRG unilaterally began exporting oil, a move rejected by Baghdad. In response, the Iraqi federal government cut the KRG’s share of the national budget, which at the time stood at 17% (excluding sovereign expenditures). Since then, the KRG has struggled to pay its public employees—who make up a significant portion of the population—on a regular basis.

Growing frustration has fueled demands for a long-term solution, as the crisis has persisted for over a decade. For instance, public employees have yet to receive their December 2024 salaries, while the KRG now plans to distribute January 2025 salaries—effectively skipping December’s payment. The Iraqi government insists it has disbursed the necessary funds and argues that the KRG has failed to meet its obligations under the federal budget law, which requires the KRG to transfer both its oil and non-oil revenues to Baghdad. However, despite producing over 300,000 barrels of oil per day, the KRG has only sent approximately 400 billion Iraqi dinars from its total non-oil revenue of 3.4 trillion to Baghdad.

The KRG, however, presents a different narrative. It claims that Baghdad’s payments fell short, forcing it to divert funds intended for December salaries to cover November’s wages. Additionally, the KRG states that it has used a significant portion of non-oil revenues to pay public sector wages and cover operational costs. Yet, there remains little transparency about oil revenue, despite the KRG admitting that nearly half of its oil income goes toward production costs and that it sells crude at roughly half the global market price.

Despite the financial shortfall affecting public employees, multiple indications suggest that KRG revenues are being diverted toward political projects. For example, KDP President Masoud Barzani recently launched a new Arabic-language TV channel, reportedly employing over 200 Arab media personnel in Erbil, at an estimated cost of millions of dollars per month. Similarly, in 2024, the KRG’s Prime Minister approved a controversial expenditure in which the Minister of Construction acquired 15 luxury Land Cruisers—valued at $1.7 million—as part of the ministry’s operational costs.

At its core, the crisis is deeply political, rooted in a broader power struggle. Baghdad has increasingly leveraged intra-Kurdish divisions to assert greater control over the region. This includes expanding its influence over Kurdish oil and gas fields, bypassing the KRG by directly paying salaries to public employees, and seeking authority over the Kurdistan Region’s largest oil fields—many of which lie outside the 36th parallel in disputed territories claimed by both Erbil and Baghdad.

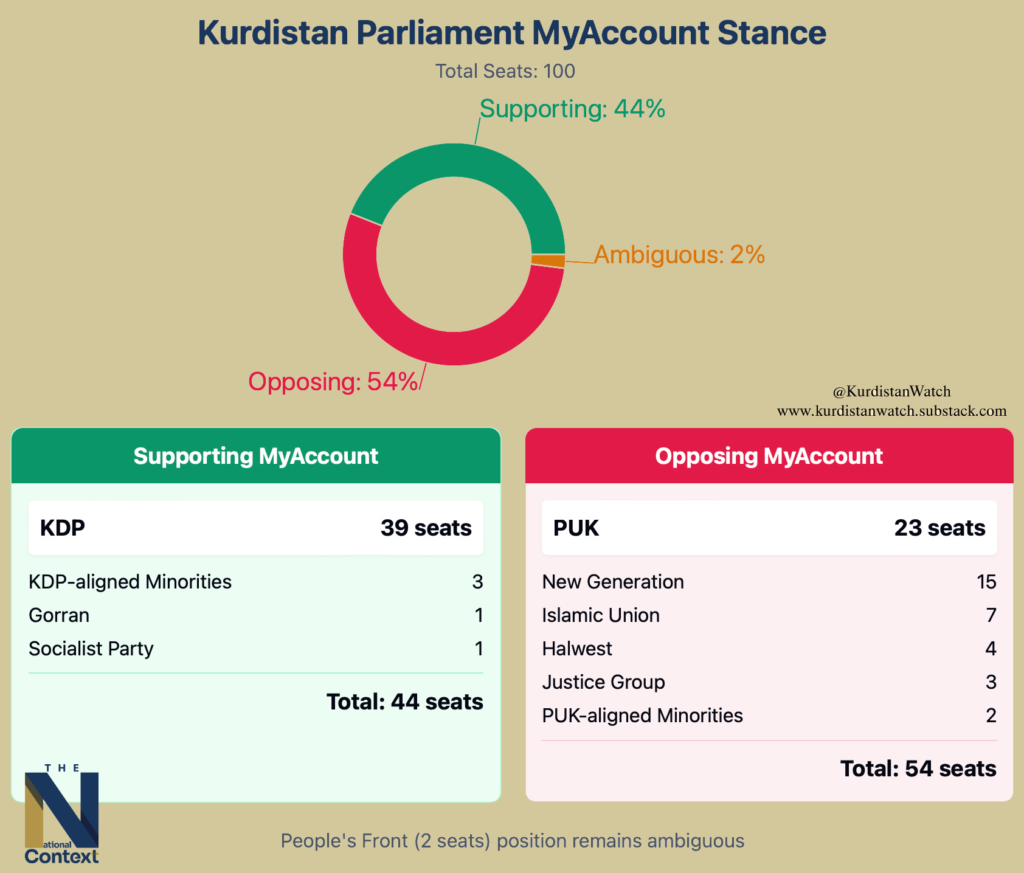

A central demand of Sulaimani’s public employees is the domiciliation of their salaries to Iraqi state-owned banks instead of the KRG-backed MyAccount system. Protesters argue that MyAccount is a personal project that primarily benefits KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani and could deepen the salary crisis. They cite a February 2024 ruling by Iraq’s federal banking authority, which mandated that KRG public sector salaries should be disbursed through state-owned banks—a ruling that resulted from a legal complaint filed by a group of Sulaimani public employees.

The KRG strongly opposes this measure, arguing that relinquishing salary distribution authority would reduce it to a mere provincial administration. Moreover, it rejects Sulaimani’s unilateral integration into Iraq’s federal banking system, fearing that such a move would fragment the KRG’s governance structure. If Sulaimani’s salaries were consistently paid on time while Erbil and Duhok continued to experience delays, it could embolden similar demands in those cities—further eroding the KRG’s control.

The KRG Prime Minister finds himself in an increasingly precarious position. Aside from his ruling KDP, even the PUK—nominally the KDP’s coalition partner—has sided with the protesters, along with all opposition parties in the Kurdish Parliament, forming a parliamentary majority.

What remains unclear is how the protests will unfold. With Iraq’s parliamentary elections approaching, both ruling Shia and Kurdish factions are likely to adopt populist rhetoric to secure votes. The PUK, in particular, may push further for salary domiciliation in Baghdad as a means to resolve the crisis within its sphere of influence. However, ongoing negotiations between the KDP and PUK over the formation of the next KRG cabinet complicate the matter, leaving the future of the region’s civil servants in limbo.