Iraq’s Sunni Politics in 2025: from Taqaddum’s Dominance to a Three-Way Contest

The early campaigns for Iraq’s November 11 parliamentary elections began well ahead of schedule, long before the official one-month window. Unlike previous rounds where appeals to cross-sectarian unity or “pan-Iraqi patriotism” were at times fashionable, this year’s campaign atmosphere is shaped far more by sectarian and regional narratives.

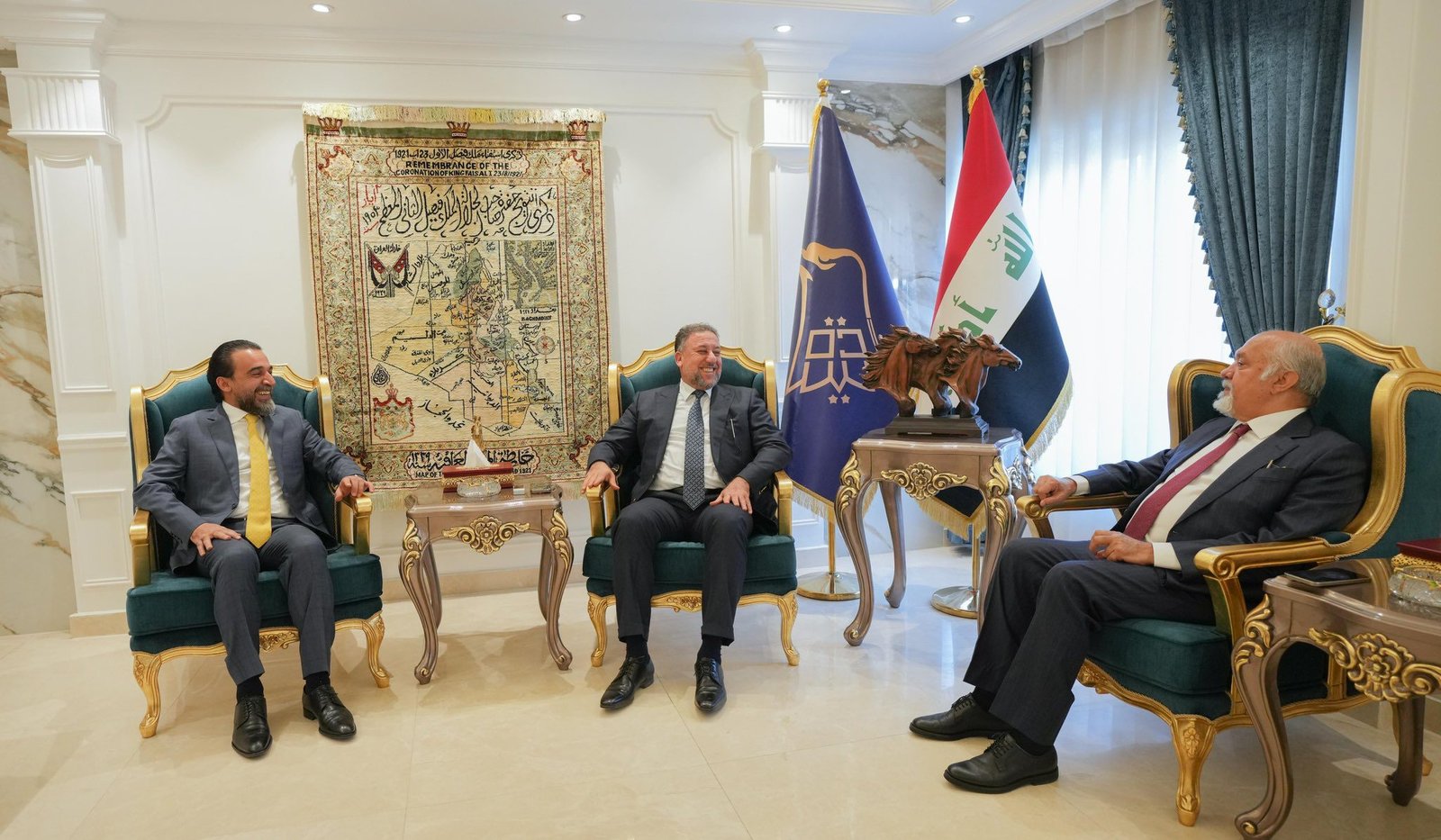

While the decisive contest remains among Shia blocs, who continue to dominate the political order, the parallel struggle within Sunni ranks is significant in shaping how Sunnis position themselves in the next parliament and how much leverage they will have in coalition bargaining. Three major leaders, Mohammed al-Halbousi, Khamis Khanjar, and Muthanna al-Samarrai, are competing to consolidate their constituencies and redefine Sunni representation in Iraq.

The Resurgence of Sectarian Politics

Among Sunnis, the geopolitical shifts in Syria and the retreat of Iranian influence across the region have fueled a sense of revived ambition. Sunni leaders now openly speak of restoring their community’s position in Iraq, with some even entertaining the prospect of claiming the premiership. Politicians such as Khamis Khanjar have leaned heavily on religious and historical symbolism, using slogans such as “We are the generation of the companions” during campaign tours, highlighting how sectarian identity is being instrumentalized in campaign rhetoric, turning the election into a symbolic struggle over which community embodies Iraq’s political and religious legitimacy.

Shia parties, in turn, have responded with an emphatic defense of Shia political dominance, often accompanied by threats and warnings. Their rhetoric stresses the need to safeguard Shia rule and end the practice of making concessions to other communities, Kurds and Sunnis in particular, on the basis that Shias constitute Iraq’s demographic majority. In this vein, Najaf’s Friday preacher, Sadr al-Din Qobbanchi, declared that the election is no longer just a political process, but for Shias represents a vital defense of religion and sect.

This escalation of sectarian rhetoric, though effective in stirring grassroots sentiment, sits uneasily with Iraq’s political realities. Since 2003, Iraq’s governing system has been structured around power-sharing and consensus, underpinned by a constitution and laws designed to enshrine partnership—even if often violated in practice. Iraq’s political order is not determined internally alone, but is also shaped by regional and international frameworks, making purely sectarian mobilization at odds with the structural givens of the post-2003 state.

The Baathist Question

One of the most contentious features of this election cycle has been the intense scrutiny of candidates accused of Baathist affiliation. The Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) significantly delayed approval of the candidate lists after a widespread campaign warning of a possible Baathist “return” to parliament. In total, 700 nominees came under investigation, including former MPs, governors, and senior administrators.

Ultimately, 335 candidates were permanently excluded under Law No. 10 of 2008, which bans individuals who held senior Baath Party or security positions. While those disqualified retain the right to appeal, the process has been clouded by allegations of pressure, bribery, and political interference. Even Haider al-Abadi, a Shia leader, acknowledged that the judicial authority overseeing exclusions was subject to “unfair competition.”

What surprised many was the sectarian distribution of the disqualified. While the narrative of “Baathist infiltration” is most prominent among Shias, documents show that more than half of the excluded candidates were from Shia lists. Out of the 335, Shia lists accounted for 151, Sunnis 141, Kurds 13, and minorities only 6. The disqualified Shia candidates came not only from Maliki’s State of Law, Badr, Asaib Ahl al-Haq’s Sadiqoon, and the Supreme Islamic Council, but also from the lists of armed groups such as Kataib Hezbollah—groups that present themselves as protectors of Shia rule.

The Sunni Political Landscape

In Sunni-majority provinces, electoral competition is concentrated around three figures: Mohammed al-Halbousi, Muthanna al-Samarrai, and Khamis Khanjar. Their sources of power, regional depth, and constituencies differ, but together they dominate the Sunni scene. The Sunnis overall compete for around 70 seats in Iraq’s 325-seat parliament.

The Taqaddum Alliance represents the political vehicle of Mohammed al-Halbousi, with its primary stronghold in Anbar province. Registered as an alliance with the electoral commission on April 22, 2025, the coalition emerged following 2020 under Halbousi’s influence as parliament speaker. The alliance lacks consistent ideological coherence or political direction, having expanded rapidly throughout Sunni areas through pragmatic positioning. This flexibility has yielded significant governmental positions for the alliance, which secured the largest share of Sunni seats in 2021, winning 37 of approximately 70 seats allocated to Sunni-majority districts.

Halbousi maintains notably close ties with UAE ruler Mohammed bin Zayed, which has afforded him considerable political maneuverability as a maverick politician who prioritizes Sunni interests through tactical alliances. His political positioning shifts between proximity to Shia parties and Iran, and alignment with Kurdish factions, though he has recently embraced nationalist rhetoric, turning against the KDP’s Barzani while allying with the PUK in Kirkuk. This shift has positioned him as a prominent critic of proposals to provide peshmerga forces with heavy weaponry such as artillery. The alliance’s discourse centers on defending the Sunni component, ensuring their representation, and rebuilding areas devastated during the ISIS conflict, capitalizing on the contrast between the sectarian violence and instability that preceded their emergence and the relative reconstruction and stability achieved under their governance.

Also read:

The Sovereignty Alliance derives its name from concepts of independence and sovereignty, closely associated with Khamis Khanjar’s personality and influence. Beyond political activities, Khanjar maintains a prominent presence in business, charitable work, and social initiatives. Internationally, he has cultivated strong relationships with Turkey, Qatar, and Ahmad al-Sharaa’s Syria, positioning himself within the broader regional Sunni bloc. He is also a close ally of KDP’s Masoud Barzani and has maintained this alliance in Kirkuk and through close political coordination across Iraq. His activities have extended to the Kurdistan Region, particularly among Arab refugees and along the Nineveh borders. While initially allied with other Sunni figures, including Muthanna al-Samarrai, these partnerships dissolved, leading to independent participation in the 2023 elections under the Sovereignty banner. Given the numerous complaints and accusations of Baathist sympathies and sectarianism directed against him, Khanjar has strategically distanced himself from direct leadership roles, preferring to function as a patron figure while his sharp statements regarding Sunni rights and criticism of Shia governance continue to generate controversy.

The Azm Alliance comprises several Sunni parliamentarians under Muthanna al-Samarrai’s leadership, who serves as a prominent representative of Salah al-Din province. The alliance includes various small organizations and regional Sunni parties, with their primary base in the Sunni-majority areas of Salah al-Din and Baghdad’s periphery. Campaign rhetoric has emphasized representation of the “Sunni component,” urging Baghdad residents to participate rather than boycott the elections, while stressing that their concerns extend beyond service provision to encompass participation in decision-making processes. Samarrai faces corruption allegations related to his membership on the Finance Committee and involvement in Ministry of Education contracts. He maintains relatively positive relationships with Shia forces as well as with Iran and demonstrates openness toward Kurdish parties through visits to Erbil and Sulaimani.

Iraqi Sunni Political Arena

Electoral Performance Analysis - November 2025

Key Performance Insights

- Taqaddum dominated with 37 seats, more than double Azm's 14 seats.

- Halbousi's alliance showed exceptional strength in Anbar (10:1) and Nineveh (8:1).

- Despite fewer votes in Salah al-Din, Taqaddum secured more seats than Azm.

- Baghdad remains the most competitive battleground with 18 total Sunni seats.

Key Comparative Insights 2021-2023

- Taqaddum lost 6 seats in Nineveh, dropping from 8 to 2 seats.

- Combined Azm-Sovereignty gained 4 seats in Salah al-Din (from 1 to 4 total).

- Taqaddum's dominance in Anbar reduced from 10-1 to 6-3 against combined opposition.

- Baghdad showed Taqaddum declining from 11 to 9 seats while opposition grew.

- Total vote shifts: Taqaddum lost 80,508 votes while Azm-Sovereignty gained 152,667 votes.

Electoral Trend Analysis

- 2023 provincial elections showed combined Azm-Sovereignty votes exceeding Taqaddum in several provinces.

- Taqaddum maintained slight advantages in Baghdad and Diyala in provincial councils.

- The separation of Azm and Sovereignty alliances after their 2021 coalition creates new dynamics.

- Electoral volatility reflects shifting alliances and regional dynamics.

Provincial Competition Dynamics

- Anbar remains Taqaddum's fortress with 90% dominance.

- Diyala shows perfect 50-50 split, indicating fierce competition.

- Nineveh's large seat allocation makes it a crucial battleground.

- Kirkuk's unique demographics favor Taqaddum's pragmatic approach.

- Baghdad's diverse Sunni population creates unpredictable voting patterns.

Competitive Dynamics and Electoral Prospects

The Sunni electoral field has evolved from the 2021 parliamentary elections to the 2023 provincial councils in ways that complicate any simple reading of “who leads the Sunni house.” In 2021, Taqaddum—built around Mohammed al-Halbousi’s leadership and organizational machine—was the clear Sunni pacesetter across the main provinces, both in votes and seats. In Baghdad, for example, Taqaddum won 139,960 votes (around 10 percent) and 11 seats, compared to Azm’s 116,308 (about 8 percent) and 7 seats, a four-seat cushion that signaled Taqaddum’s urban reach beyond its Anbar base. That edge was even more emphatic in Anbar, where Taqaddum’s local dominance translated into 201,439 votes (46 percent) and 10 seats against Azm’s 77,097 (18 percent) and 1 seat. In Nineveh, Taqaddum again outran Azm, securing 123,080 votes (15 percent) and 8 seats to Azm’s 58,831 (7 percent) and 1 seat, while also picking up one seat in Kirkuk on 42,290 votes (10 percent), with Azm absent there. In aggregate across the study’s seven-province Sunni theater, the 2021 scoreboard captured the structure of that moment: Taqaddum 37 seats and more than 640,000 votes to Azm’s 14 seats and around 418,000 votes.

By 2023, the picture had shifted. Azm split, Sovereignty emerged as Khamis Khanjar’s vehicle, and the Sunni vote began to distribute across multiple lists, often eroding Taqaddum’s earlier margins without eliminating its presence at the top of the table. The most dramatic swing occurred in Nineveh, where the 2021 Taqaddum lead (8 seats to Azm’s 1) collapsed into a Sovereignty-led field in 2023: Sovereignty won 3 seats, Taqaddum 2, and Azm 1. In effect, a six-seat advantage for Taqaddum in 2021 flipped to a one-seat edge for Sovereignty two years later. The numeric analysis underlines why: Taqaddum’s 2021 to 2023 vote delta in Nineveh was minus 48,892, while Azm and Sovereignty combined expanded their share there.

The capital Baghdad tells a different but equally instructive story. Taqaddum’s 2021 lead over Azm narrowed from four seats to about one seat in 2023 once Azm and Sovereignty are treated as the two vehicles carrying what used to be a single bloc. Azm and Sovereignty combined added more than 21,000 votes compared to Azm’s 2021 baseline, while Taqaddum eked out a modest 859-vote gain. The net effect: Taqaddum still present, but no longer sitting on a comfortable cushion in the capital.

In Anbar, Taqaddum remained first in 2023 but with visible softening at the margin. The study records a Taqaddum vote delta of minus 38,337 versus 2021—still a lead, still machine strength, but the direction of travel is notable for a party whose legitimacy has been anchored in provincial reconstruction and patronage. Salah al-Din stayed tightly contested: Taqaddum converted a 2021 outcome where Azm led on votes but trailed on seats (Azm 1 seat, Taqaddum 2) into a 2023 result of Taqaddum 4 seats versus a runner-up on 3 seats, with Taqaddum’s own vote count down by 5,704 on 2021—a reminder that seat arithmetic can move even when absolute support softens.

Diyala emerges as the quintessential three-way grinder. In 2021, Azm was ahead on votes but tied Taqaddum 4–4 in seats; by 2023, Sovereignty and Azm each held 4 seats, with Sovereignty ahead on votes—yet Taqaddum actually posted the clearest vote gain here (+11,666) compared to 2021. The mix of balanced seats and divergent vote trajectories underscores how list distribution and thresholds shape outcomes in a province where no Sunni alliance has a decisive organizational edge.

Implications for Sunni Bargaining Power

Stepping back, the period can be seen as a gradual redistribution of Sunni political weight: Taqaddum keeps a prominent position, especially in Anbar and competitive footprints in Baghdad and Salah al-Din, but its 2021 dominance is no longer singular. Azm and Sovereignty, together, narrowed gaps or flipped provinces (Nineveh being the standout), which diversifies post-election bargaining channels with Shia and Kurdish partners even as it dilutes the prospect of a unified Sunni negotiating front.

Two mechanics are worth emphasizing for the November 11 election. First, vote deltas do not translate linearly into seats. Baghdad and Salah al-Din show how small swings can meaningfully compress seat gaps, whereas Nineveh demonstrates how a coalitional split (Azm/Sovereignty) can reallocate seats away from a single dominant Sunni list more rapidly than vote erosion alone would suggest. Second, organizational form matters. Taqaddum’s setbacks can be traced to internal fragmentation and service-delivery perceptions in some provinces, and to a leader-centric model that has not been fully institutionalized—vulnerabilities that rivals have exploited with targeted provincial strategies and sharper messaging tuned to local grievances.

In sectarian terms, none of this dislodges the structural reality that Shia blocs remain the decisive arena for government formation. But the re-balancing inside the Sunni camp matters for what comes next: it will shape the Sunni share of parliamentary leadership posts, committee chairs, and ministerial portfolios, and it will set the tone of Sunni bargaining with Shia and Kurdish partners. A Taqaddum that retains first place but with thinner cushions enters negotiations with less unilateral leverage; a more competitive Azm/Sovereignty axis gains negative power—the power to block, to withhold, to raise prices on support—even if neither can claim comprehensive primacy. In practical terms, the Sunni outcome on November 11 is not about choosing a prime minister; it is about pricing Sunni participation in a Shia-led government and allocating Sunni representation in ways that either rebuild coherence or entrench fragmentation, with direct implications for service delivery and stabilization in Sunni-majority provinces.