Kurdistan as a Campaign Weapon in Iraq’s Shiite Elections

Although Iraq’s general elections are officially scheduled for November 11, campaigning has begun weeks in advance. Rival Shiite and Sunni forces have already deployed every weapon in their political arsenal. In this contest, the Kurdistan Region has once again become a convenient instrument, pressed into service in the internecine struggles of Shiite parties and in their rivalry with external opponents.

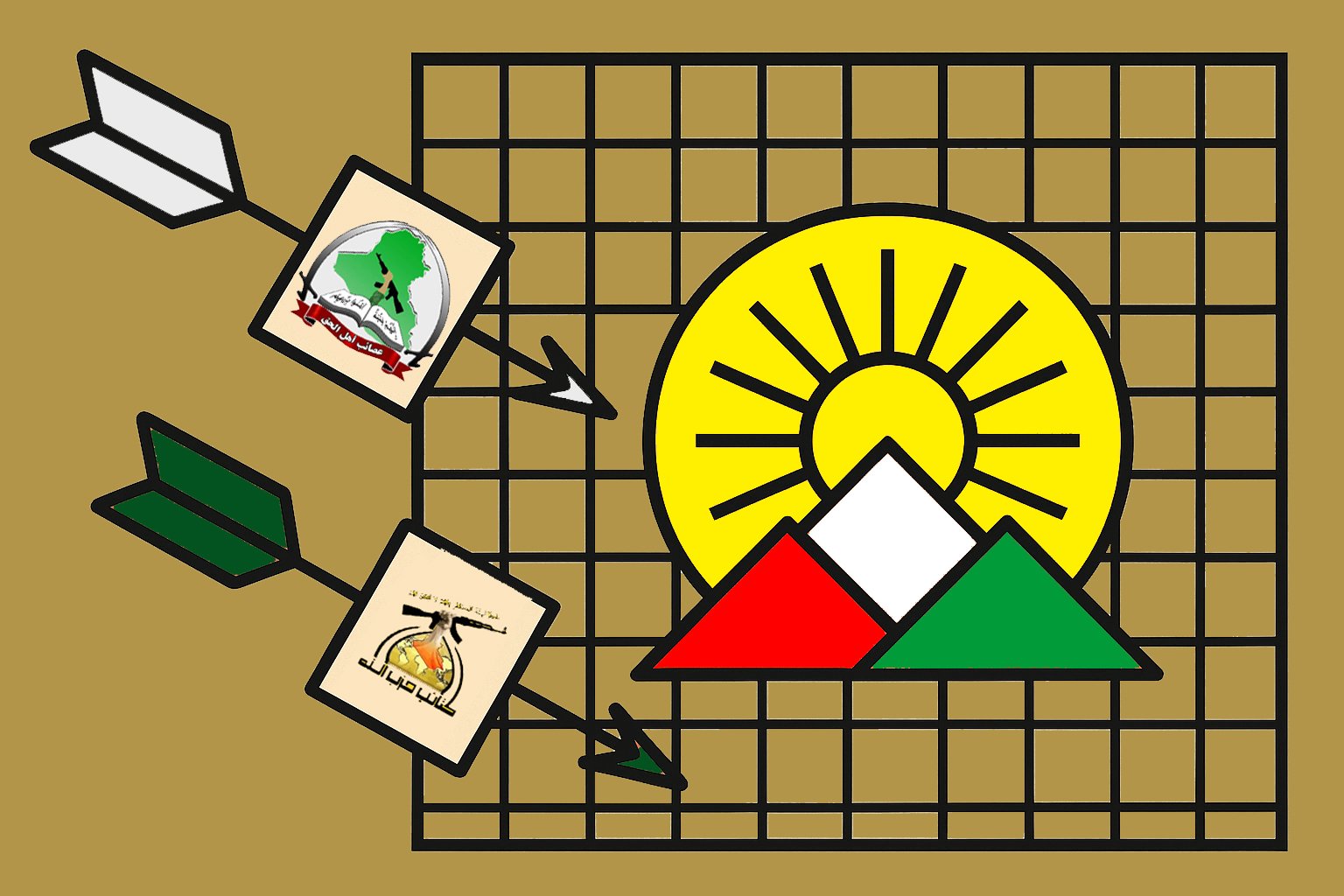

Among those most active in shaping this discourse are Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. Both attach great importance to media operations, and both increasingly target the Region as a recurring theme. This analysis—leaving aside the government-aligned discourse of Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani’s own list—focuses on how Shiite factions frame the Kurdistan Region during the campaign.

Hashd and Baath as Electoral Instruments

The Shiite Coordination Framework is contesting these elections through several competing lists. The main players are al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development list, pitched as the incumbent’s platform for a second term, and his rivals: Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law, Hadi al-Amiri’s Badr Organization, Qais al-Khazali’s Sadiqoon, and the State Forces alliance of Ammar al-Hakim and Haider al-Abadi.

To mobilize their bases, these forces emphasize three key files:

- 1. The Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) law,

- 2. The specter of Baathist return, and

- 3. Disputes with the Kurdistan Region.

Each file corresponds to one of Iraq’s main political pillars—Shiite, Sunni, and Kurd—and is instrumentalized accordingly.

First: The Sacred Codification of Popular Mobilization Rights

On its face, the contentious draft law on the PMF’s Rights and Privileges seeks to codify the entitlements of some 236,000 fighters and employees, backed by an annual allocation of three trillion dinars. Yet its true significance resonates on multiple levels:

The Popular Imperative: This legislation directly touches the economic lifelines of tens of thousands of families whose votes constitute the bedrock of their electoral success.

The Sacred Symbol: Within Shiite collective consciousness, the PMF has transcended its military origins to achieve an almost mystical status—a “sacred” institution whose legitimacy cannot be challenged without risking political apostasy.

The Political Reality: The transformation of the PMF from security apparatus to “guardian of the political order” represents perhaps the most significant institutional evolution in post-2003 Iraq. As an indirect bulwark of Shiite supremacy, particularly following the region’s geopolitical upheavals, it embodies both sectarian identity and state power.

To dramatize their support, around 100 Shiite MPs announced they would vote in military uniform. Yet beneath this theatre lies deep factional discord: who will control the PMF’s leadership? How will its vast budget be divided? Of Iraq’s more than 180 Shiite MPs, only about 100 have actively signed on, leaving many ambivalent or conditional.

Second: The Baathist Specter as Political Cudgel

De-Baathification, a mechanism born in Iraq’s 2003 transition, still lingers as both sword and shield. In this campaign, al-Maliki has made its revival a centerpiece, insisting that Baathists must be barred from candidacy.

The Accountability and Justice Commission has summoned 404 candidates over Baathist ties; perhaps 250 will be excluded. Though this represents just 5% of the nearly 8,000 contenders, the weight is magnified because several are seasoned parliamentarians with established constituencies.

Critics note the arbitrariness: why were many of these same figures permitted to serve in previous parliaments? Explanations diverge: some argue leniency was tolerated before but is now ending; others warn of genuine fear within Shiite circles of systemic change or even Baathist resurgence—fears stoked by regional shifts, particularly in Syria.

The file is not purely political but also financial: bribes reportedly smooth or harden Baathist cases. Sunnis view it as a proxy war, waged through legal instruments rather than open political competition. While both Shiite and Sunni candidates have faced scrutiny (145 Shiite, 94 Sunni, 11 Kurdish), public rhetoric overwhelmingly frames Baathism—and by extension terrorism and betrayal—as Sunni-linked.

Major Shiite Electoral Alliances

Iraq Parliamentary Elections • November 11, 2025

329

Total Seats

29M

Eligible Voters

10-15

Shiite Lists

69

Baghdad Seats

Development & Construction

Mohammed Shia al-Sudani

60-100

Projected Seats

Key Components

Al-Furatayn, al-Aqd al-Watani, al-Wataniya, tribal & civil forces.

State of Law

Nouri al-Maliki

Strong

Outlook

Key Components

Dawa Party, Fadhila Party, Muntasirun, Sayyid al-Shuhada.

Sadiqun List

Qais al-Khazali

Rising

Outlook

Key Components

Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq, Salahuddin tribal components, gov positions.

Badr Organization

Hadi al-Amiri

Security

Outlook

Key Components

Badr wing, Interior Ministry networks, Hashd leadership.

State National Forces

Hakim-Abadi Axis

Moderate

Outlook

Key Components

Hakim legacy, Abadi experience, protest allies, civil society.

Tasmeem Alliance

Asaad al-Eidani

Regional

Outlook

Key Components

Basra base, economic figures, potential Sadrist support.

Third: The Kurdistan Region as Electoral Ammunition

Since the unraveling of the Kurdish–Shiite alliance during Nouri al-Maliki’s second term (2010–2014)—driven largely by oil disputes and regional disagreements—the “Kurdistan file” has become a recurring campaign weapon for Shiite forces. In the coming elections, it is expected that budgetary and oil-related issues will again be brandished in this way, offering Mohammed Shia al-Sudani the chance to project himself as a strong leader willing to confront the region and to counter rivals who deride him as overly conciliatory.

Though the dispute itself is hardly new—it dates back to 2012—it reliably intensifies in the final year of each government, as seen under al-Abadi, Abdul-Mahdi, al-Kadhimi, and now al-Sudani. This is the point when the “honeymoon period” ends, electoral calculations eclipse governance, and appeasing the Shiite street takes precedence. Shiite parties are well aware that Kurdish partnership will be indispensable in the coalition-building phase after votes are counted. But before the elections, gestures of compromise toward Erbil carry a populist cost. Consequently, meaningful dialogue is typically deferred until after results are announced and coalition negotiations commence.

Al-Sudani’s Second-Term Strategy

Al-Sudani seeks reelection under his own banner, aiming to cement his position for 2024–28. His political messaging deliberately courts Iraq’s middle classes—merchants, civil servants, military officers, and state beneficiaries—with particular attention to Baghdad’s influential constituencies.

Al-Sudani’s campaign architecture rests upon carefully constructed pillars:

Diplomatic Neutrality: Positioning Iraq above regional conflagrations, particularly the Gaza conflict and Iranian-Israeli tensions, appealing to war-weary citizens seeking stability over ideological adventurism.

Personal Branding: His decision to lead the Baghdad ticket personally transforms the election into a referendum on his leadership, a high-stakes gamble that could either consolidate or shatter his political future.

Media Dominance: Leveraging state media apparatus while cultivating cyber influence through social media personalities, creating a comprehensive information ecosystem favorable to his narrative.

Welfare Expansion: Highlighting institutional growth and social monitoring networks, with ministerial candidates boasting oversight of more than two million beneficiary families—a formidable electoral constituency.

Infrastructure Achievement: Emphasizing Baghdad’s visible transformation through reconstruction projects that have tangibly improved urban life.

Coalition Diversity: Assembling a heterogeneous alliance spanning tribal leaders, Shiite militia commanders, sitting ministers, provincial governors, and parliamentary veterans.

On the Kurdish question, however, al-Sudani prefers quiet pressure over fiery rhetoric. His strategy has been to squeeze the Region on oil, revenues, and salaries—without theatrics. He has offered only muted remarks to outlets like Asharq al-Awsat. Yet his list betrays internal incoherence: some allies, such as Hanan al-Fatlawi, demand radical decentralization of oil and salaries, while others like Baha al-Araji speak conciliatorily of the region. This lack of a unified stance may fracture the bloc after the polls.

The Loyalist Forces: Architects of Anti-Kurdish Sentiment

If al-Sudani treads cautiously, Iran-aligned factions do not. Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq dominate the anti-Kurdish narrative through their extensive media apparatus. Their outlets systematically monitor Kurdish opposition channels, selectively amplify Kurdish voices critical of their own authorities, and blend genuine reports with conspiratorial claims.

Drawing on these sources, they construct an image of the Kurdistan Region framed through the following themes and messages:

Narratives in Kata’ib Hezbollah Media

Through their media platforms, Kata’ib Hezbollah consistently portray the Kurdistan Region in starkly negative terms. Drawing on opposition Kurdish outlets, select guest commentators, and curated monitoring of regional news, they circulate the following messages:

- – The Kurdistan Region constantly pressures Baghdad for money, channeling funds into its own electoral campaigns.

- – The Region behaves as though it were an independent state, contradicting the constitution and political process. Oil revenues and border customs, they claim, flow directly into ruling party coffers without oversight.

- – American Congressman Joe Wilson’s statements against Iraq are financed by the Kurdistan Region, serving Washington’s interests and laying the ground for sanctions on Iraq.

- – While there is a campaign to fragment the PMF, other armed groups—including the Peshmerga—are left unchallenged.

- – Continued oil smuggling from the Region, they warn, risks “catastrophic consequences” and international punishment for Iraq.

- – The KRG is accused of violating its agreements with Baghdad, refusing to hand over oil, and using attacks on oil fields as a pretext. It is painted as opaque, untrustworthy, and deliberately obstructionist.

- – Prime Minister al-Sudani is accused of stalling the disbursement of salaries to Kurdistan Region employees in order to serve regional authorities. Baghdad, they argue, transfers money to “corrupt Kurdish officials” rather than directly to workers.

- – Oil shipments to Turkey are hidden under layers of cement and other goods to disguise smuggling operations tied to ruling parties.

- – The KRG grants Baathists safe haven, protecting their families, facilitating their movement abroad via Erbil Airport, and enabling secret meetings with Kurdish leaders under official protection.

- – Ruling parties are accused of exploiting the salary file for private profit, inflating payrolls with fictitious names while genuine employees remain unpaid. The federal government, they insist, must intervene to correct the situation.

Narratives in Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq Media

Asa’ib media—through both television and online outlets—echo many of these themes, adding their own layers of messaging. Among the recurrent claims:

- – Erbil harbors Baathists and Baghdad gave it evidence, but it wasn’t willing to discuss it.

- – Erbil and Turkey have a fifty-year agreement giving Ankara many privileges in Kurdistan, including building military bases.

- – An Iranian newspaper reports: The route for Israeli Mossad to reach Kurdistan is a corridor that worries regional countries.

- – The Region has been in political and administrative vacuum for a year due to parliament expiring and delayed new government formation.

- – Opposition says: After 23 years of self-rule (since 2003), Kurdistan has become criticized for failing to provide basic services and allowing uncontrolled weapons to spread.

- – Kurdistan’s problems continue… drought and reduced production, electricity cuts imposed in Sulaimani.

- – In Kurdistan there are arrest campaigns and judicial and media suppression targeting anti-corruption opposition. There are also suspicious connections, including with the “Zionist entity.”

- – Kurdistan is under suppression; freedoms are being strangled.

- – A journalist’s arrest shows escalating suppression of freedom in Kurdistan.

- – Kurdistan is in its weakest state with a management crisis.

- – The Kurdistan Region benefits from the salary crisis. The PUK agrees with Baghdad’s view.

- – Kurdistan’s government continues smuggling about 250,000 barrels of oil daily; those benefiting from the process don’t allow legitimate exports.

- – Drones are used as excuses for self-defense against oil agreements.

- – Kurdistan’s government turned “Hiwa Hospital” into a mass grave through deliberate neglect. Medicine meant for this hospital gets smuggled to Turkey.

- – Four trillion dinars outside the budget… Oil theft numbers in the Region are huge and half goes to foreign companies.

- – All smuggling border crossings are on Kurdistan’s borders.

- – In Kurdistan, oil is treated like personal property; authoritarian rule causes the crises.

- – Kurdistan’s university graduates emigrate because of difficult conditions.

- – Due to corruption… the Region lacks water and electricity with no hope for the future.

- – New oil smuggling methods have been found that are different from old ones.

- – Parliament Security: The cause of unorganized weapons in the Region is the regional ruling forces.

Analyzing the Media Strategy

A close reading of the media campaigns run by Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq reveals a carefully orchestrated narrative strategy. Several recurring techniques and messages stand out:

Mixing Truth with Propaganda: Using real information but mixing it with false claims to shape public opinion, without balance or checking other sources.

Selective Focus: Highlighting Turkey’s role in Kurdistan while deliberately ignoring Iran’s role in Kurdistan’s oil sales.

Damaging Kurdistan’s Image: Trying to destroy the positive reputation Kurdistan once had as more developed than central and southern Iraq, by emphasizing every crisis, even natural ones like drought.

Attacking Good Institutions: Damaging the reputation of even respected institutions like Hiwa Hospital, known as an important cancer treatment center in Iraq.

Weaponizing governance failures: Salary disputes, press restrictions, and mismanagement are repeatedly emphasized to argue that life in the Region is no better—indeed, no freer—than in the south.

Casting Kurdistan as a threat: The Region is portrayed as Israel’s refuge, Turkey’s client state, and simultaneously a haven for spies and Baathists.

Weakening al-Sudani: The Prime Minister is accused of negligence and of colluding with Kurdish leaders, an effort designed to tarnish his credibility within the Shiite electorate.

Taken together, this discourse serves two overarching objectives:

Justifying Shiite dominance and Baghdad’s centralism: By insisting that Kurdistan is equally corrupt, dysfunctional, and oppressive, Shiite factions normalize failures in the south and excuse the shortcomings of centralized rule. If the Region is no better, then Baghdad’s flaws are neither unique nor disqualifying.

Mobilizing populist hostility toward Erbil: By framing Kurdish authorities as authoritarian, corrupt, and aligned with Israel, these narratives seek to inflame the Shiite and Arab street against any reconciliation or pragmatic cooperation with the Region—making hostility itself an electoral asset.

This sophisticated media manipulation represents more than just election tactics—it threatens the basic compromises that Iraq’s democratic system depends on by turning normal political differences into existential battles.